Landing at Victoria International Airport, in the capital of British Columbia, felt like returning to my second home. It was at Pearson College, near Victoria, where I completed school and first learned how to scuba dive six years ago. On my recent trip to the Pacific Northwest I thus had the opportunity to revisit the past and explore more of the Salish Sea.

Vancouver Island has some of the best cold-water diving on earth. But despite flying into Victoria, I took a ferry to Anacortes, Washington State the next day. I was not surprised to find equally good diving across the Strait of Juan de Fuca on the Washington coastline. However, the purpose of my stay in the US was not to explore beautiful dive sites. I joined Julie Barber, the 1999 North-American Rolex Scholar, and her team of fisheries scientists to conduct a survey on sea cucumber density around Whidbey Island and Puget Sound. Yes, sea cucumbers — you didn’t misread if you picked up on this weird and wonderful species and ‘fisheries’ in the same sentence. Despite what we may think about them, sea cucumbers makes it on the menu of many restaurants in the Far East. Commercial fisherman thus collect ‘cukes’ on dives and export them to Asia.

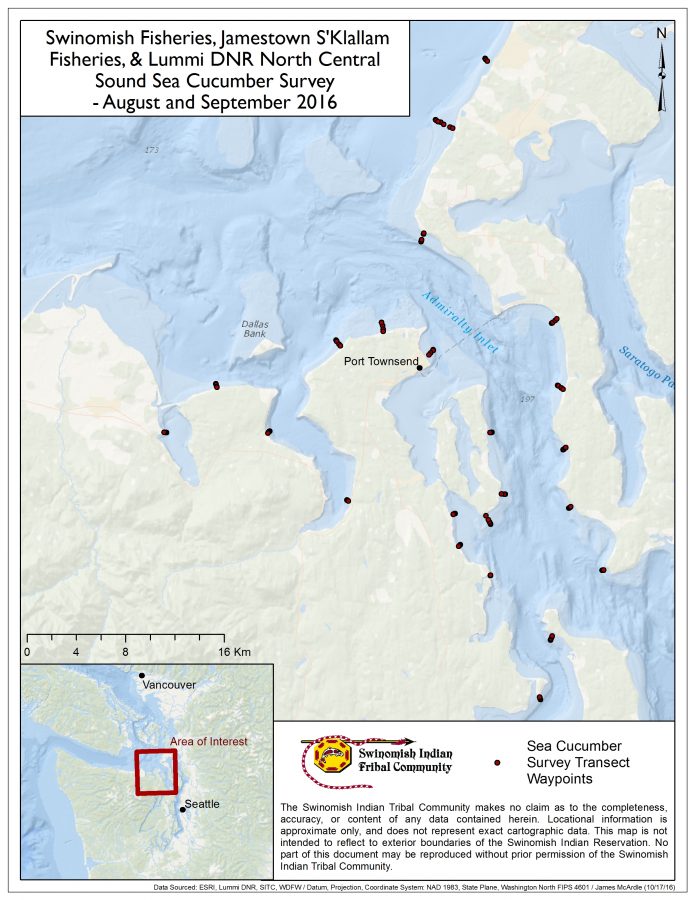

Another fascinating fact about this Washington State fishery is that the Native American tribes hold 50% of the fishing quota. This is unique in North America, based on court-affirmed tribal treaty rights from the mid 19th century. As their own sovereign nations, the tribes thus have to co-manage, with Washington State, the commercial fish and shellfish stocks. Therefore a team of five scientists working for the Lummi and Swinomish tribes and I counted cucumbers along several transects. These were 200-1,500m long and ran from the twenty to the six meter depth contours. The tribes’ fisheries scientists and Washington State Department of Fisheries are currently processing the results to set next year’s quota.

Some of the dives were challenging to say the least. Swimming perpendicular to the shore, the tidal current often pushed us to the side and away from our transect line. I soon learned to throw all buoyancy scuba skills overboard and crawled over the seabed when the current was at strongest. On the longest transect of 1,500m, we were slightly frustrated to find only one cucumber. But even stretches of no or few cucumbers added to the database and information for successful fishery management. On top of that, I learned a lot of valuable scientific techniques for fisheries stock assessment. Thank you, Julie and the team from Swimonish for this great learning experience.