Whilst in Orkney in early July I began to hear a lot about the marine renewable energy projects taking place there. Orkney has been described as a global centre of excellence for the marine renewables industry, and this is thanks to the profusion of expertise, investment and enthusiasm currently gathered – and still gathering – within Orkney. With an avid interest in how the sea is being used as a resource, specifically in a sustainable manner, I took the opportunity to return to Orkney and gain insight into the marine renewables industry. I wanted to learn how the industry was operating and evolving on Orkney.

I found the current projects to be exciting and novel: they are pushing technology and knowledge boundaries. They are providing a positive outlook for a realistic supply of green energy. The Scottish government has set an impressive target of producing 100% renewable energy by 2020 following the success of reaching and surpassing its 2011 target of 31%. The seas around Orkney will be a crucial resource when it comes to achieving this new target. The Crown Estate has granted leases for specific areas adjacent to the mainland, which are currently being capitalized upon by a number of different companies. However, rather reassuringly the Crown Estate has not yet granted leases for the Pentland Firth as no technology has proved itself capable of withstanding the strength of the tidal flow to an extent allowing for the safe attachment of devices to the seabed. With a potential to generate 1.6GW of electricity in the sea surrounding Orkney the future is bright for marine renewables here. It is evident that any major industry expansion will be carefully planned, monitored and established. For me it is great to witness the sea being used as a significant resource, whilst the respect the sea deserves is maintained.

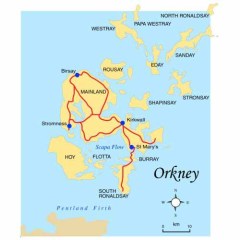

In 2004 the European Marine Energy Committee (EMEC) opened in the Orkney town of Stromness. Today EMEC is credited with creating purpose-built wave and tidal device testing facilities at specific locations adjacent to the Orkney mainland. Two facilities allow companies to test their wave and tidal devices in open sea, whilst another two facilities – known as scale facilities – allow testing of prototypes in more gentle conditions and with reduced logistical complexity. These test sites have attracted a range of companies to Orkney.

Whilst I was in Orkney Pelamis were testing their P2 Pelamis device; Wello were testing their Penguin device; and Aquamarine Power were testing their Oyster 800 device. All are designed to capture wave energy and yet all have different designs.

Pelamis 2 can best be described as a large floating tube of interconnecting segments. It generates electricity from the “motion at each hinged joint being resisted by hydraulic cylinders which pump fluid into high pressure accumulators”. This allows “electrical generation to be smooth and continuous” (http://www.pelamiswave.com/our-technology/the-pelamis).

Wello’s Penguin device resembles a ships platform that has been barged from every angle! Wello describe the Penguin as looking and moving like a penguin and claim “this is part of its strength and gives us confidence that it’s the right shape to survive at sea and harness plenty of energy from the waves.” Their website describes the Penguin generating electricity through “the hull rolling, heaving and pitching with each passing wave. This motion is used to accelerate and maintain the revolutions of a spinning flywheel housed inside the hull. The flywheel drives an electric generator to produce electricity, which is then exported via a subsea cable.” (www.orkneymarinerenewables.co.uk )

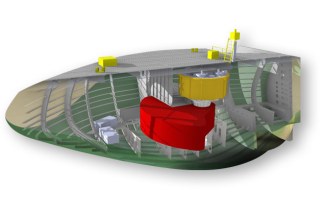

The Oyster 800 from Aquamarine Power is “a buoyant, hinged flap which is attached to the seabed at depths of between 10 and 15 metres”. The Oyster “pitches backwards and forwards in the near shore waves. The movement of the flap drives two hydraulic pistons which push high pressure water onshore via a subsea pipeline to drive a conventional hydro-electric turbine.” (www.aquamarinepower.com)

I believe the assortment of designs currently being tested is positive for the industry. Some may argue that money and expertise should be combining to produce one optimal device. However, with competition brings vigor – a desire to prove and achieve. Orkney is providing test sites, and as such Orkney should be attracting different companies with differing designs and ideas. There are different designs; there is enthusiasm; there is excitement; and there is a future for marine renewables in Orkney.

The success to date of the marine renewables industry in Orkney is thanks to a number of different factors. Orkney Islands Council Marine Services Department provide essential and effective regulation and control in terms of planning and providing the infrastructure for the industry to be able to work and develop. I met with Michael Morrison, Business Development Manager at Orkney Marine Services, at the Headquarters in Scapa, near Kirkwall. His stance on the current projects is positive – new piers are to be constructed in the near future to cope with the increased need for ships to service the testing facilities. New jobs have, and will continue to be, created. In addition, Orkney’s main town of Kirkwall is emerging as the industrial hub, whilst Orkney’s second town of Stromness is emerging as the intellectual hub. The positives spurning from these projects are reaching throughout the islands.

The success of the marine renewables industry on Orkney has also been thanks to the presence of the International Centre for Island Technology (ICIT) in Stromess, part of Heriot-Watt University. Having been located here since 1989 the expertise base of the ICIT has expanded hand in hand with the emergence of the renewables industry here. By carrying out advanced research and consultancy in all matters surrounding marine resource management the companies testing devices in Orkney have an affluent expertise base to call upon.

In order to get the wave and tidal devices in the water requires an array of logistics. Orkney based firm Aquatera specialises in operational and environmental support, as well as forming an important link to the local community. I met with Gareth Davies, Aquatera’s managing director, to discuss the work being done by Aquatera. Although Aquatera does not make the final decision regarding where a test site or device can be established, the company does inform the decision makers through a range of different survey techniques. These include noise monitoring, sedimentology, wildlife observations, seabed sampling, side scan sonar and geologic surveying to name but a few! Gareth explained how Aquatera are trying to make their survey results and final reports more appealing and engaging – the company does not want to see reports merely filed on shelves. Aquatera want people to recognise and appreciate their reports, to want to read them. Hence Aquatera use a lot of visuals in their reports – such as sea bed mapping. In addition, community consultation takes the form of open meetings and public displays – rather than public notices and access to long reports.

What is great about the marine renewables expansion on Orkney is the extent to which local knowledge and involvement has been vital. Orcadians have been relying upon the sea for centuries. As such there is a wealth of knowledge and logistics already in place to cover all aspects of the sea including drilling, cable laying, construction, towing, navigation and operational control. In addition, Michael Morrison pointed out to me that local opinion must be listened to and respected because to understand the sea and its influence in a specific region takes years of knowledge and experience. The tides and waves surrounding Orkney do have great potential to generate electricity, however, they are powerful and intricate and this must be appreciated if any device is to succeed.