At any one time I find myself with an array of remarkable diving opportunities on offer. From dives that would effortlessly impress the late Jaques Cousteau – and no doubt every one of his many grandchildren – to courses taught by world leading instructors and dive centres, decision making becomes a routine challenge. Choosing between reef diving in the Egyptian Red Sea, versus drysuit diving in the North Sea, sounds like the least challenging of decisions.

Dives made on coral reefs have registered as some of the most stunning and vibrant dives of my life, and yet it was the unfamiliarity of cold-water diving that drew me back to the more unforgiving latitudes of the world.

Novel learning opportunities saw me return to Scotland and my friends in Orkney. With the switch of my PADI Pro status from Divemaster to Instructor imminent, it is important for me to experience PADI courses in action. Having previously worked as a Divemaster in warm-water locations, it is cold-water instruction, and particularly drysuit instruction, which I remain unaccustomed to. As always, the entire staff of Scapa Scuba dive centre were extremely willing to help, and Sara had my name on the day-sheets ASAP.

For three days I joined Stef as he taught a PADI Advanced Open Water course to Anke and Dave, a Belgian couple who were using drysuits for the first time. Learning to use a drysuit is difficult, especially when you are a new diver. What’s more, teaching courses to new drysuit divers can be exhausting: it requires an investment of time and effort far and beyond what is necessary for warm-water dive instructing. I was fortunate to shadow Stef – an instructor who is clearly passionate about delivering comprehensive courses. It’s not a tick the boxes affair. It was very heartening to witness the transformation in Anke and Dave. While struggles, frustrations and exhaustion dominated the first two days, come day-3 both surfaced as happy and competent divers with a genuine desire to return to Orkney and dive the wrecks of Scapa Flow. To achieve this during a three-day cold-water course requires determination from everybody: a willingness to learn and a true talent to teach.

Novel learning opportunity number 2 involved a (heavy) twin-set. Diving Scapa Flow, coupled with the knowledge I gained during my GUE Fundamentals course, have made me more aware of twin-sets and their uses. I am sure my future diving career will involve twin-set diving, and I am certainly equipped for it having been sponsored with an amazing set of Apeks Tek3 regs. To quote Patrick Keeley: “they look like the Lamborghini of regs” – an apt description. It was time to double up.

Even though I completed my Fundamentals course using a single tank, many of the “fundamental” skills are transferable and apply to the majority of dives. Since completing my GUE Fundamentals course with Rich Walker I haven’t had many opportunities to practice these skills, despite Rich inspiring me to pursue further GUE diving. Throughout my basic twin-set training I was finally able to refresh my fundamental skills with Stef’s help: remaining in trim being the golden rule. I regularly break it.

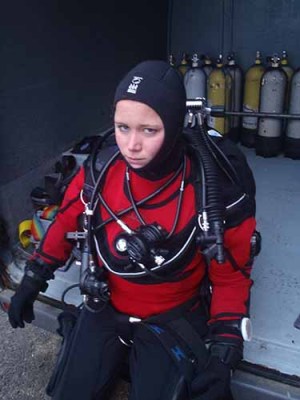

Equipment configuration, valve drills, s-drills and arm contortions were all practiced in the classroom after allowing an appropriate length of time for the aftermath of an evening spent in the Flattie Bar to subside. Kirstie – who keeps the Scapa Scuba shop shipshape – acted as my buddy during the scenarios, and together we managed to grasp the basics of twin-set diving under Stef’s patient guidance. With my Halcyon harness adjusted; my Tek3 regs screwed into place; bolt snaps tied to hoses, and all drills mastered, we called it a night.

With Kirstie back on shop duties on Sunday, Stef and I took to the shallows of Stromness harbor. As somebody who is still struggling to master “trim”, you might say observing Stef’s flawless trim positioning during every single moment of every single dive is good experience for me. I disagree.

After wriggling and writhing and bending my arm into an array of inventive positions while attempting to reach the isolator valve – repeatedly losing “trim” in the process – I have to stop before my attempts cause me to reach a perilous state of exasperation. Storming off under-water is not an option, unfortunately. And of course, as I recompose myself for yet another attempt to reach that elusive isolator valve, my eyes are met with trim personified. A torment. And then I watch “intently” as Stef demonstrates, with utter refinement no less, how to reach the isolator. Turning the other way, I embarked on my 99th attempt.

Still, I am the first to admit that mastering trim and buoyancy and conducting all skills in an unambiguous nature will lead to success. To achieve this takes practice, you need to regularly dive the set up. It is good to be challenged as a diver, not least when you are an instructor and need to be able to empathise with a fraught student. This is what makes the scholarship year so unique – I have realised I have a vast amount still to experience, learn, attempt, pass, fail, love and hate when it comes to diving. Diving is boring when you reach complacency.