My year as the OWUSS European Rolex Scholar officially started in mid-July after handing in the first draft of my MSc thesis on anthropogenic disturbance of whale sharks in the Maldives, with two more months of writing to be continued after my return. Instead of heading to the tropical latitudes, however, my first experience took me to a slightly colder place, and as far away from the equator as physically possible onboard a sailing vessel: the Arctic circle. Equipped with a backpack full of woollen garments, a rucksack filled with Marzipan chocolate and peppermint tea, and a waterproof bag containing my most important piece of kit – my absolutely amazing Fourth Element Argonaut Drysuit – I joined Barba Norway’s 2021 Arctic Sense Mission for the circumnavigation of Svalbard by sailboat under the expert directive of Captain Andreas B. Heide.

Arctic Sense was a collaborative four-month scientific and communications expedition setting sail on a 3,000 nautical mile investigative voyage to the polar Atlantic onboard ocean conservation platform S.V. Barba. Starting and ending in Barba’s home port, Stavanger, Norway, it saw a multinational teams of researchers and storytellers sail via Svalbard, Jan Mayen, the Faroe and Shetland Islands, Edinburgh and London to research, document and share the challenges faced by marine life in the region. The focus of the expedition were keystone Arctic and sub-Arctic whale species – the sentinels of our ocean.

Not many vessels travel around the entire archipelago, and even fewer sailboats attempt to do so due to rapid weather shifts and unpredictable movement of sea ice. For me, the challenge of learning how to plan and execute a wind-powered expedition in Arctic waters was what first sparked my determination to get onboard Barba, further fuelled by my own aspirations to own a sailboat and conduct both research and dive expeditions from it in the future. I always wanted to work in the polar regions, but finding sailing vessels able to take on the monumental task of navigating in uncharted icy waters proved to be difficult. That is, until I stumbled across Barba a few years ago, after reading about Captain Andreas B. Heide’s connection with Orcas in Norway and have been inspired by his level of dedication to and expertise in Arctic sailing. Being able to join his crew as the 2021 OWUSS European Rolex Scholar after an extraordinarily difficult year away from the ocean was nothing short of a dream come true. And a big undertaking! As non-intrusive platforms, sailboats not only enable unique wildlife encounters, but also uniquely embed their crew in the elements they are navigating. The wind and water, not time, dictate the rhythm of the day and determine the vessel’s progress. In the Arctic, ice is not only an additional factor, but a powerful force shaping a vessel’s course. That is precisely what our three weeks at sea onboard the SY Barba, a small 37 ft Janneau Sun Fast, were determined by.

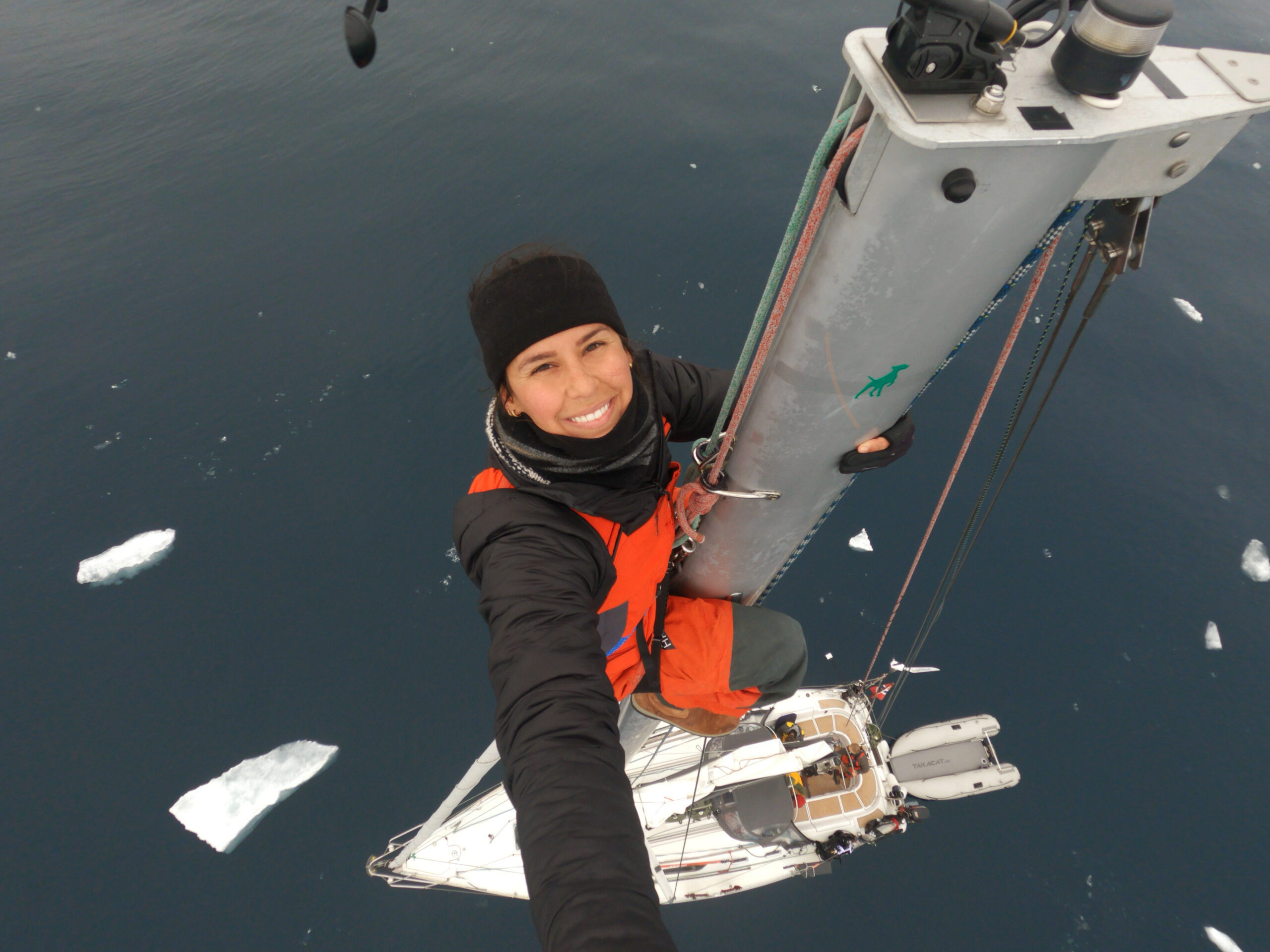

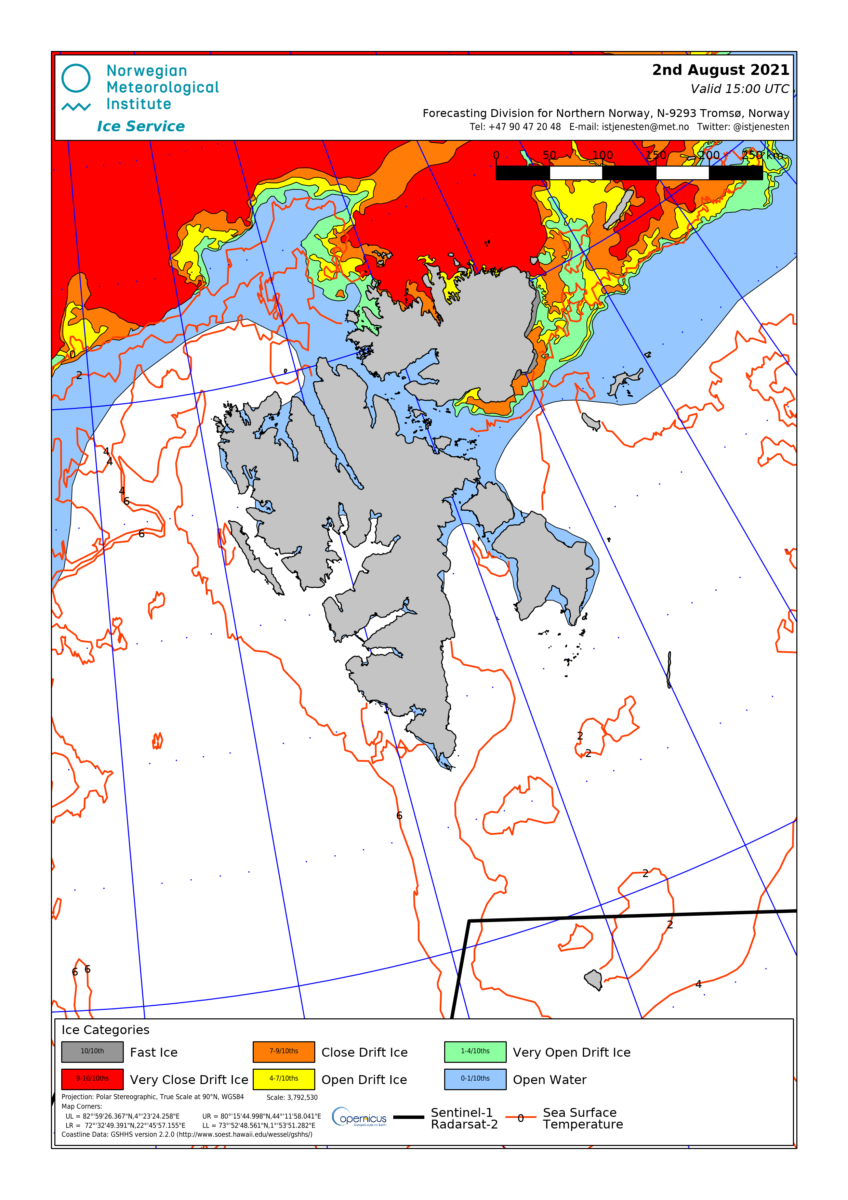

Covering critical distances was vital for our progress around the island of Svalbard and influenced our ability to stop the vessel in scientifically relevant areas for the deployment of acoustic monitoring systems and Lidar-equipped drones to study Arctic whale populations. After all the crew arrived, multiple bags were reduced into one (after all, space is very limited on such a small boat!), it was time for planning. Looking at the map of the rugged outlines of Svalbard, the wind forecast and the ice charts issued by the Norwegian Meteorological Institute we knew we had to push North as much as we could in the first week. The “we” consisted of 6 people: Norwegian Captain Andreas B. Heide in his iconic red wool beanie, a young Custeaou in many ways; Italian whale scientist Giulia Ercoletti who was head over heels in love with Orcas; US American filmmaker Mark Romanov, who specialised in aerial and underwater cinematography and worked on the Attenborough-narrated documentary “Whale Wisdom”; Norwegian Photographer and drone pilot Tord Karlsen, a seasoned member of the Barba crew often found on top of the mast; Swedish sailor, wintersport champion and soon-to-be nurse, Ylva Carlssen; and me, a German-Turkish conservation scientist, OWUSS European Rolex scholar and diver. We were a colorful bunch indeed, with varying skillsets and expertise that beautifully complemented each other – all brought together by our love for sailing, whale research and the protection of polar environments. Inspired by each other and wrapped up in warm layers, we promptly departed the port of Longyearbyen – the world’s northernmost settlement – in foggy but exceptionally calm water conditions and sailed towards the higher latitudes, observing small walrus colonies we passed along the way. Until that point, I had never seen a walrus in the wild and in their natural environment; my only encounters with them had been in captivity. To think that these animals were once nearly pushed to the brink of extinction by extensive hunting in the region seemed like an abstract concept after witnessing their abundance along the coastline. It also gave me a sense of hope that the damage done to eco-systems by human exploration (and greed) can be reversed with sound environmental management.

Indeed, traces of human exploration were visible everywhere in this remote place. Recovering animal populations and wooden hunter cabins dotting the barren landscape served as reminders of our troubled past and the impact we have had on this ecosystem. The crumbling remnants of old whaling stations, carcasses of beluga whales and remains of blubber ovens we visited in Virgohamna, Ingebrigtsenbukta and Smeerenburg – all of which used to land thousands of whales a year during the whaling period – served as powerful symbols of the shift in our relationship with the natural world. Once regarded as nothing but mere commodities that were hunted for their oil and blubber, whales now occupy the hearts of Svalbard’s locals, the scientists that study them and the tourists willing to spend a fortune to observe these magnificent creatures in the waters up here.

While we saw many reminders of the dark past faced by whales, we also very incredibly lucky to see many of these gentle giants living and breathing next to our sailing vessel. The dangers and wonders that were between the surface dictated our everyday life onboard Barba. The 31st of July marked a milestone in my life – as a marine conservationist and sailor. Struck by the onset of mild sea sickness that crept up on me during strong winds and choppy seas, I went to sleep, only to be woken up a few hours later by the captain with the words “blue whale, next to the boat”. I don’t remember ever getting dressed so quickly. There it was, my first ever blue whale. A gentle giant, dwarfing our vessel, leaving all of us in complete awe amidst the silence of a vast Arctic landscape. I cannot put into words how I felt in that moment. Being in the presence of the world’s largest animal, watching its towering blows and graceful movements was a humbling and transformative experience. The wind carried the spray of its exhale onto the boat and our faces were covered by little drops of fishy whale breath. In some cultures such an experience is said to leave one blessed for the rest of their life. As the whale circled around the boat, we sent up a drone equipped with LiDaR to measure its body condition using MatLab and made sure to take photos of the whale’s dorsal fin and fluke for ID purposes. LiDaR stands for Light Detection and Ranging, and is a remote sensing method that uses light in the form of a pulsed laser to collect measurements. Simply put, a LiDaR scanner calculates how long it takes for beams of light to hit an object or surface and reflect back to it. I had come across LiDaR very frequently in the modules focusing on novel conservation technologies during my MSc degree in Biodiversity, Conservation and Management. Being able to learn how to use this technology for the study and protection of marine mammals while being in the field was an absolutely brilliant opportunity. Shortly after our encounter slowly came to an end, we couldn’t believe our eyes when we discovered three more blue whale blows on the horizon, several kilometers away. Utterly delighted, we sailed towards them and just in the moment when we thought we had lost sight of the giants we were chasing, two blue whales surprised us by surfacing directly next to the boat. They followed us for a little while, keeping a consistent speed next to us before diving down and disappearing into the blue. The powerful sound of their sudden blow, still reverberated in my bones hours later.

Blue whales were not the only ocean giants we encountered. With access to some of the most remote parts of Svalbard’s archipelago Barba also served as a science support vessel for research teams that did not make it into the field this year due to Covid. By coincidence, one of the scientists for whom we changed a camera trap at a kittiwake colony turned out to be Dr. Tom Hart, from the University of Oxford! He was one of my lecturer’s teaching novel conservation technologies and sharing his insights on remote sensing of large marine bird colonies. It’s a small world, up there in the Arctic! A few months ago he had left a camera trap on the edge of a cliff that is now home to thousands of birds.

We took on what initially seemed to be a simple task of retrieving this camera trap (and later on, returning it to Oxford in my suitcase!), only to be surprised by a polar bear mother nursing her cub. Luckily, she did not approach but she did register our presence and continued observing us from a distance. While they are magnificent creatures, they are also known to hunt down humans and in Longyearbyen stories are told of a polar bear that stalked and followed to fishermen for days before ambushing them.

Indeed, polar bears surprised us throughout the expedition. A few days earlier, once we had sailed into Claravogen, we were met by a polar bear walking onshore. It noticed us and started swimming towards the boat. That meant even at anchor, we picked up the watch system again. But this time it wasn’t ice watch, but polar bear watch instead. I spent many hours on deck scanning the surface of the water and the land to watch out for any polar bears approaching our boat, and to deter them before a difficult situation could arise in the first place.

It was a privilege to be in the presence of these predators, and also deeply saddening to know what future lies ahead for them if our civilisation does not manage to halt climate change. Polar bears rely on sea ice to hunt and travel far distances using ice sheets. With the acceleration of climate change, however, we are now losing Arctic sea ice at a rate of almost 13% per decade, and over the past 30 years, depriving bears of key habitat and feeding opportunities. The oldest and thickest ice in the Arctic has declined by a stunning 95%. New research shows the Arctic Sea ice to be melting faster than predicted by any of the 18 computer models used by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPPC). If emissions continue to rise unchecked, the Arctic could be ice-free in the summer by 2040. These numbers where very present in my head as we kept course towards the pole and as we observed the number of icebergs around us slowly increasing with every mile we traveled. I could not possibly imagine this place without them and felt incredibly humble to be able to witness this incredible frozen landscape.

From the bay of Claravågen, we continued to sail up North, able to see the outlines of Svalbard’s infamous Sjuøyane (7 islands) along the way, until we hit dense sea ice at 80 degrees 32 minutes North and could not push north any further. We had made it. We had sailed as far north as we could. We had reached the northernmost point possible. It was a magical moment worthy of celebration. There are no words that could possibly describe how I felt witnessing the vast white landscape that stretched out in front of us, knowing full well that we had successfully sailed here on a small sailboat originally built for pleasure cruising in the Mediterranean.

After carefully assessing the movement of a large floating piece of sea ice, Captain Andreas and I were deployed on it to collect a few water samples while the boat circled around us. It was a rather surreal moment beautifully captured by Tord and Mark who came with us on the dinghy. Standing there on the ice, I was reminded of its fragility of the Arctic ecosystem and the climatic importance of sea ice.

10h of sailing through fog later we anchored off Nelsonøya (Nelson Island) to shelter from increasing winds and rest. The island is named after the well known englishman Horatio Nelson, who served as midshipman aboard HMS Carcass, under Captain Skeffington Lutwidge. The Carcass was one of the two bomb vessels sent under the command of Constantine John Phipps to Svalbard during the 1773 Phipps expedition towards the North Pole. After 2h on ice watch, observing the drifting pieces of ice and watching out to see if any of them get dangerously close to our boat, it was finally time to prepare my dive gear for a dive with the Captain! Visibility was good, there were no currents that could pose a risk and only one large piece of ice was moving, but away from us. Diving at the pack-ice a day ago had proven impossible due to rapid movement of the ice and the uncharted depth below the boat. Being only a small sailboat, we did not want to take any unnecessary risk and waited for optimal water conditions and the safety provided by a bay to take our first dive. We sat down below deck, planned our dive to every small detail, visualised a map of the area, established a safety plan and then jumped off the back of the boat once we put on our kit and meticulously checked everything was in order. With water temperatures ranging between 0-4 degrees and uncharted waters below us perfect preparation was key and there was no space for mistakes. And of course, there was the added challenge of diving from a small sailboat with ropes, sheets, portable fuel tanks and other equipment in the way and very little room to move around gear!

It was an exhilarating experience. A year ago, I was dreaming off diving off a sailboat in the Artic, and here I was, actually turning a dream into reality. The moment my body hit the water, I felt the cold surround me and a burning sensation on the part of my face that were not covered by my mask or hood. I felt alive and I like I had finally truly “arrived” in the polar North. As much as I love sailing, the technical challenges and the freedom that comes with it, there is absolutely nothing that compares to diving. I was smiling ear to ear. This was my first ever drysuit dive in the ocean – and I was lucky enough to do it at 80 degrees North. After our buddy checks, a few minor gear adjustments and acclimatisation to the freezing water around us, Captain Andreas B. Heide and I descended. I exhaled and merely looked at the magical seascape around me in awe. It was so different from the tropical and Mediterranean ecosystems I had previously dived in. Initially so barren, yet strangely so alive. We made our way to to the wall of sea ice that had been pushed into the bay by the wind. A perfect opportunity to explore the ice with minimal risk. A small tunnel system had formed by the pieces that had been wedged together and we spent the next 20 mins slowly exploring it and admiring the myriad shades of blue around us.

Every few minutes Captain Andreas B. Heide and I would check in on each other, signalling “ok” and determining the direction we would go. It was blissful. The silence, the colours, the movement of the Arctic kelp (some of which we hauled up on the anchor and prepared as a snack alongside our dinner), the visibility – without the cold and limitations of diving on normal air, I could have happily spent the entire day admiring the beauty of nature. We continued exploring the coastline of the bay, adhering strictly to our dive plan and recording a few videos along the way. As neither Andreas nor I had heated undersuits, despite all our wooden layers – inevitably – we started feeling cold after about half an hour of being in the water and started our controlled ascent to the surface.

At the surface we were greeted by the excited crew who kindly helped Captain Andreas B. Heide and me to lift up our dive kit and had already prepared hot tea to help us warm up.

After our time at the pack-ice it was time to sail South and return to Longyearbyen. To do so, we had to pass the 150km long and up to 60km wide Hinlopen strait between Spitsbergen and Nordaustlandet, known to be notoriously difficult to pass due to sea ice accumulating in the strait and often blocking passage, trapping vessels for days. As a fibreglass boat with limited supplies onboard this was the scenario that had to be avoided at all costs through careful planning and expert navigation by our Captain. The ice charts we had downloaded from the Norwegian Meteorological Institute showed that the pack ice had moved further north and that Hinlopen was ice-free.

With little wind, we decided to motored south into Hinlopen only to be surprised by a mixture of sea ice and glacial ice that initially seemed to be scattered and became denser as we held course. Finally, we hit a dense belt of frozen chunks that blocked our way. To find a way through the ice and avoid getting surrounded by it and potentially trapped, we hoisted Giulia up the mast and sent a drone up. After 8 hours of zigzagging our way through ice and hitting closed waterways, we finally managed to escape our frozen labyrinth and enter clear blue waters. Perhaps my favourite quote from Captain Andreas B. Heide’s field notes was the following, that perfectly captured our situation: “As for the ice charts, we had the latest valid one. The problem is that the Norwegian Meteorological Institute only issues ice charts weekdays, assuming that polar explorers, as they do, rest during the weekend.” Well… we did not have time rest as we had to continue South to make it around the southern cape of Svalbard in a favourable weather window – otherwise we would have risked having to anchor for multiple days to wait for strong winds to pass while potentially also putting the vessel in harms way with ever shifting ice in the Hinlopen strait.

After successfully sailing out of Hinlopen we were rewarded with one of nature’s greatest spectacles, and yet again, a living reminder of how quickly the Arctic is changing with increasing weather: Bråsvellbreen, a glacier on the southern part of Nordaustlandet with unbelievable 45 kilometre long stream southwards from the ice dome Sørdomen of Austfonna that is ultimately debouching into the sea on the south coast. The ice cliff of Bråsvellbreen is about 180 km long, interrupted only by very few, small rocky outcrops, making it the longest glacier front of the northern hemisphere.

INSERT CLOSING PARAGRAPH.

Thank you to the Our World Underwater Scholarship Society and Rolex for enabling my participation in a bold expedition like this in the first place and making dreams come true! I am incredibly grateful to my sailing inspiration and Arctic hero Captain Andreas B. Heide for offering me a spot on the one and only SV Barba and allowing me to sail to the polar North with him and his team! It was an adventure and a learning experience that is impossible to forget. I also want to thank all the amazing sponsors for their generosity, particularly Fourth Element for the amazing Argonaut drysuit that got sea-tested for the first time under ice, Suunto for my amazing dive computer, Halcyon and Reel Diving for the fantastic diving equipment that waited for me at home when I returned from Svalbard, as well as Reef Photo and Video, and Nauticam for my underwater camera gear that I cannot wait to set up and put to use on my next scholarship adventure with the distinguished photographer Saeed Rasheed at Red Sea Diving Safari in Egypt.