My October and November were almost entirely marine mammals, their medicine, rescue, rehabilitation, and research. With a bit of shark and turtle medicine squeezed in!

And what better place would there be to gain experience in this field than California, with its coastlines being the home to many different Marine Mammal species: From Pinnipeds, to Cetaceans, to Sea Otters! So I decided to visit a number of outstanding institutions in this field: The Marine Mammal Center in Sausalito, the Costa Lab at Long Marine Laboratory of the University of California Santa Cruz, and the Monterey Bay Aquarium.

I already apologize beforehand for some nerding in this blogpost, but I was so in my element while these experiences, that I really wanted to share my fascination 🙂

The first institution that I worked with was The Marine Mammal Center in Sausalito, the largest Marine Mammal Teaching Hospital in the world! With their extensive and world-leading Rescue, Rehabilitation, Research, Conservation and Education Programmes, The Marine Mammal Center (TMMC) was a key destination for me.

I was able to assist the daily clinical work of the veterinarians and veterinary technicians under the lead of Dr Cara Field, assessing, anaesthetizing, taking diagnostic X-rays and ultrasounds of the pinniped patients.

While I was there we also had a very special patient of a species that isn´t treated very often at TMMC, but which I had worked with already earlier in the scholarship year: An Olive Ridley Turtle, Donatella, named by the TMMC staff, who was found cold-stunned in Californian waters, which is much further north than their normal range. This can occur because the water temperatures in California this season were warmer due to currents from the south, misleading the turtle into a region that usually has much colder water all around. As a poikilothermic, or cold-blooded, reptile, these colder waters slow down the complete metabolism and therefore unfortunately also the ability of the animal to maneuver itself back to warmer waters. She was found floating motionless on the surface of the ocean, luckily Donatella was brought to TMMC, where the vets and vet technicians slowly started warming the environment around her and therefore also her body temperature, while administering saline fluid. At the same time her blood values were watched carefully to ensure a healthy equilibrium, which has to be maintained by warming her very slowly. Fortunately, she showed very quick progress and after a few days we could even have her swim in one of the pools for a few minutes at a time.

The main species treated at TMMC of course were marine mammals of all kinds. Serving more than 600 km of Californian coastline, TMMC´s main hospital can accommodate up to 290 animals at the same time, first and foremost pinnipeds like California Sea Lions, Harbour Seals, Elephant Seals, Northern and Guadalupe Fur Seals, that need veterinary care. They also respond to cetacean, or sometimes even turtle strandings or entanglements, too.

TMMC relies on a very large number of volunteers, who help in every “department”, and are trained for their tasks thoroughly. Every year, they accept vet students from all over the world for clinical internships, and they also have a programme that invites and teaches graduated veterinarians from less-developed countries with a special interest in Marine Mammal Medicine, so as to give them the means to be able to potentially set up a Stranding Response programme in their home country.

Besides being with the Veterinarians themselves, I also got to speak to different departments, such as the Department of Education, Pathology, Research, and also the Rescue Office.

In the Rescue Office I learned that for a successful Rescue, not only the Veterinarians, but also many other people play a vital role. The order in which a Marine Mammal incident is responded to is the following: when the public becomes aware and is concerned about an injured or distressed animal, they can call the Rescue Team´s office, who, through very specific questions and counting on a whole lot of experience, can often make a first evaluation of the situation through the phone. They then coordinate the Field-Rescue Teams, who are each responsible for specific regions, and who head out to the scene to evaluate the situation. If necessary and feasible, regarding weather, tide and animal population-specific conditions like the position of the animal in the landscape and within the colony, they capture the animal and transport it to the main hospital in Sausalito. Nevertheless, often the animal can also be helped on-site, which would be the ideal situation to spare the animal a whole lot of stress and keep the human interaction and interference with these wildlife animals as small as possible.

In case an animal requires more in-depth medical attention or even surgery, the animal is transported to the hospital. After a thorough examination by one of the vets upon the animal´s admittance, it is then discussed within the vet team what medical approach will be taken. The fully equipped clinic makes surgeries possible, which range from eye-surgeries, to orthopaedic surgeries, to abdominal surgeries and more.

The most common cause for admittance into the hospital in most Pinniped species is malnourishment after maternal separation, which occurs often if the mother dies, or even too-close interaction of humans and their pets with the pups, who are then abandoned by their mother. These pups are then fed-up and trained in fish-school until they have the foraging skills and body condition to be released back into the wild.

Nevertheless, entanglement in abandoned fishing gear or plastic debris, as well as injuries through boat strikes, are other very common causes for admittance into the hospital. Unbelievably, but sadly it is true, that some animals even come in having been shot with a gun by fishermen due to suspected competition over fish resources.

Another concern, which I had not heard much about before, is Domoic Acid Intoxication, which initially finds its origin on the bottom of the food chain, when a toxic algae bloom ( red tide) occurs due to for example unusually warm sea temperatures. Invertebrates like mussels, clams and crustaceans then filter the neurotoxin from the water, and are eaten either by a marine mammal directly, or are being consumed by fish, which are then being eaten by the marine mammal. Along this chain, the amount of toxin becomes more and more concentrated.

This process is called bioaccumulation, and puts the marine mammals on the top of the food chain at the highest risk, consuming a high amount of toxin. Depending on the amount they have accumulated in themselves, the animals can either recover reasonably quickly and easily from the lethargy, disorientation and seizures when being given anti-seizure medication or, at the worst, they could have even already suffered from the degradation of the Central Nervous System (Limbic System), which could possibly lead to the death of the animal.

At TMMC, there are also necropsies being performed daily in the Department for Pathology, of animals that were found stranded or dead already, or of animals that had to be euthanised or that died at TMMC, to find the cause of death. During these necropsies, valuable information can be gathered and samples are taken that are then added to TMMC´s world´s largest marine mammal tissue bank, which is also open to being used for anybody who needs it for specific research.

I was able to assist in 2 necropsies of Harbour Porpoises, and 3 necropsies of California Sea Lions, one of which I witnessed being put down due to an irreparable paralysis of a big part of its lower body. As unfortunate as euthanasia is in animals, it is the most animal-friendly solution, especially for an animal in the wild, with no chances of recovery and rehabilitation. Another visiting vet student and I were fortunate to get the chance to practise blood draws after these necropsies in different marine mammal specific body locations (very different to the animal species we learn on at vet school!), as well as a draw of cerebrospinal fluid. To practise the draw of these fluids, which can be used for the diagnosis of several illnesses, will help us to strengthen our practical skills for later handling of living animal patients.

During the necropsy of the sea lion, we found that the paralysis was due to a severe injury to the spine, potentially caused by a boat strike.

What I found most impressive, was that the necropsies could all be viewed openly through a glass front by the general public who were visiting TMMC, so that all sides of the work at TMMC are communicated, showing clearly the consequences of man-made dangers and impact towards Marine Mammals, adding in a very important educational value.

At TMMC we had several school groups come through and visit, watching us carry out necropsies and see the daily work in the rehabilitation area. These students came through a 3-month educational programme, which the extensive educational department at TMMC have set up, giving school teachers the opportunity, knowledge and materials to teach different aspects of marine science, all, in the bigger picture, evolving around the patients at TMMC. As a highlight, the students would visit TMMC at the beginning, and at the end of this programme, giving them high motivation to learn because they could draw the direct experience and relate to the charismatic marine mammals in every aspect. To see the enthusiasm and also concern of the young students about the wellbeing of the hospital´s patients proved the effectiveness of this outstanding programme.

As the next destination, I travelled down to Santa Cruz, where I was able to assist the PhD student Arina Favilla from the University of California, Santa Cruz, in her fieldwork through the Costa Lab at the Long Marine Laboratory.

Arina is researching thermoregulation in relation to the deep-diving behaviour on Northern Elephant Seals, a species which can dive to an impressive record depth of 1500 m at times on their long annual migrations between Californian and Arctic waters. To explain the amazing ability of these seals to maintain an adequate core temperature even in cold water temperatures at depths, but without overheating while “exercising” under their very thick thermo-protective blubber layer, Arina chose the method of a Translocation experiment to gather data.

The protagonists of this experiment were juvenile Elephant Seals from the Colony in the Ano Nuevo Reserve just 30 minutes north of Santa Cruz, who gather on the beach there to moult in autumn every year. We made use of this behaviour and the incredible ability of Elephant Seals to find their way back to the colony, to track the seal to Monterey, which lies just across a big bay from Ano Nuevo Reserve. What is so special about Monterey Bay, though, is that a very deep Canyon reaches very close to shore in the middle of the Bay, allowing the seal to deep dive on its way back to the moulting place at the Ano Nuevo colony, even over this relatively short distance.

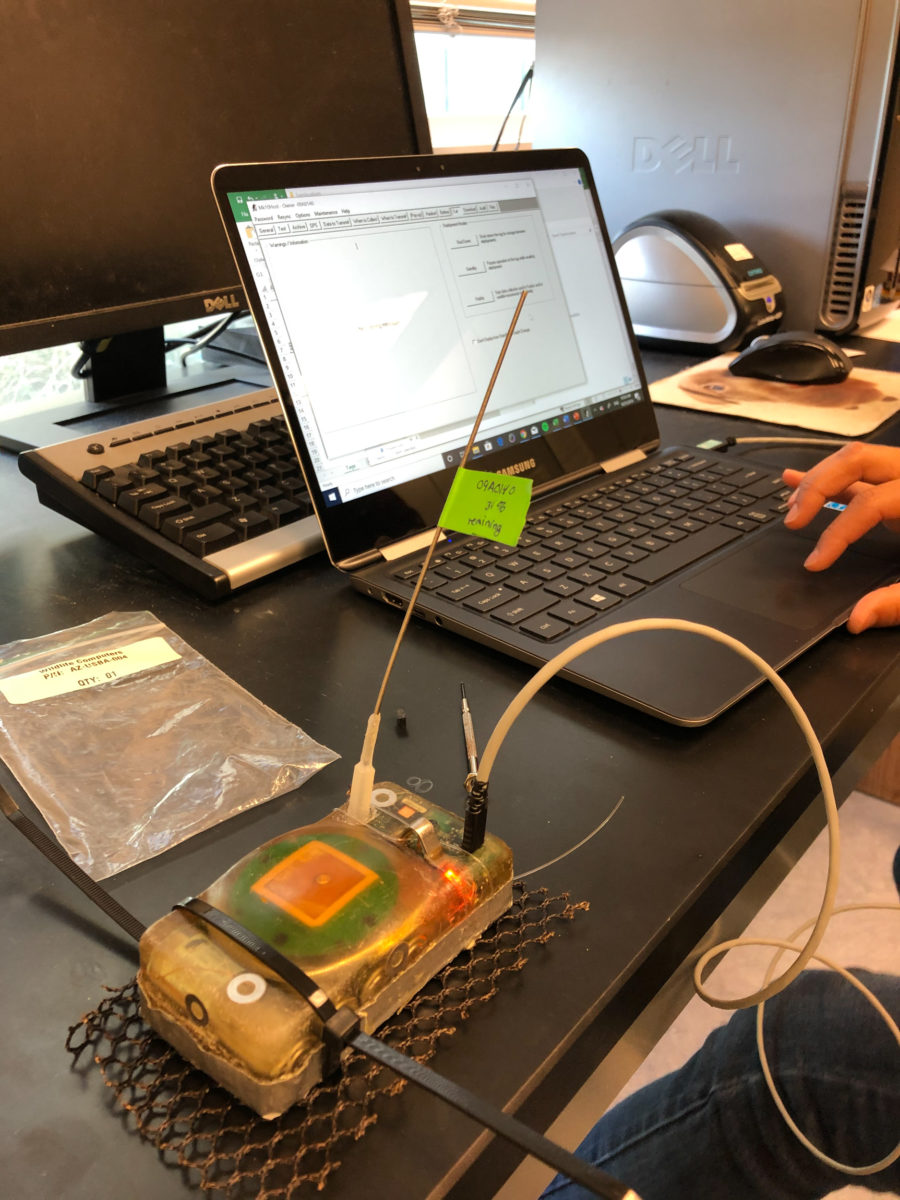

In order to find out about the deep-diving behaviour in relation to time, depth, and the physiological processes for the exchange of temperature between the seal and the water, our chosen protagonist-seal would carry a few instruments with it which measure and store all the needed information. The first instrument was going to be a satellite tag, which would help us to determine the location of the seal as soon as it spent a sufficient time on the surface, which is when the tag would send its location to a satellite and our computer.

Furthermore, this tag gathers data about the diving depth through measuring the water temperature and the amount of light in specific intervals. As the second instrument, the seal would carry heatflux biologgers, which measure the heatflux between the seal´s body surface and the water in key areas, just behind the pectoral flippers and on the sides of its cone-shaped body.

The third instrument would be thermistors, who measure the temperature in the outer, the middle, and the inner part of the seal´s blubber, indicating a vasodilation/constriction of the blood vessels in these parts, a suspected method of control of the core temperature by flushing or closing up the blood flow.

So we headed out one evening to choose a seal of suitable size and weight out of the juveniles on the beach of Ano Nuevo, who would help us gather the needed data. The next day, we took photos of the seal´s body shape from many angles, in order to develop a model using photogrammetry. Then, we installed all the instruments on the seal, and drove to Monterey with it, where it quickly hopped back into the water and started its way north, back to the colony.

Thanks to the satellite tag, we could follow the seals journey on the computer, and our seal was actually exceptionally fast, having swum back in less than 2 days, much faster than the seals which Arina had worked with the season before. I got very enthusiastic, as this would mean I could unexpectedly even help to recover the instruments and retrieve the information recorded on them, closing my assistance in the field experiment together with Arina. But unfortunately, our seal then suddenly decided to take a “small” detour, heading back south, even past Monterey, past another Elephant Seal colony on the Big Sur coast, and all the way to the Catalina Islands in front of Los Angeles. This journey in the end took our seal a few weeks, before Arina was finally able to organise a trip to the islands, where she could recover the instruments with the valuable data on them, which the seal kindly gathered for us on its way to its desired moulting place, which obviously wasn´t Ano Nuevo Reserve…

All in all, it is to say that it was a very valuable and at the same time incredibly exciting experience to be able to help in the field work with Elephant seals, contributing a little part to Arina´s PhD research on the physiology and behaviour of this pinniped species – thank you so much, Arina, for letting me be part of this, and for teaching me so many things in such a short time! I am very curious what you will find out by the analysis of all the data that was gathered…

If you are just as curious as me, please feel free to follow Arina´s blogs, also on the 60 degree North Science blog of the Alaska Sealife Center, where she learned all about Marine Mammal tagging through Markus Horning, who I was lucky enough to get to know during my stay at the Alaska Sealife Center earlier this year as well!

The third institution which I visited was the Monterey Bay Aquarium and its Resident Vet Dr. Michael Murray, a world-renowned Sea Otter specialist. The MBA has set up an outstanding Sea Otter Rescue and Rehabilitation programme, which has helped tremendously in the successful reestablishment of a large and healthy Sea Otter population in the Monterey Bay.

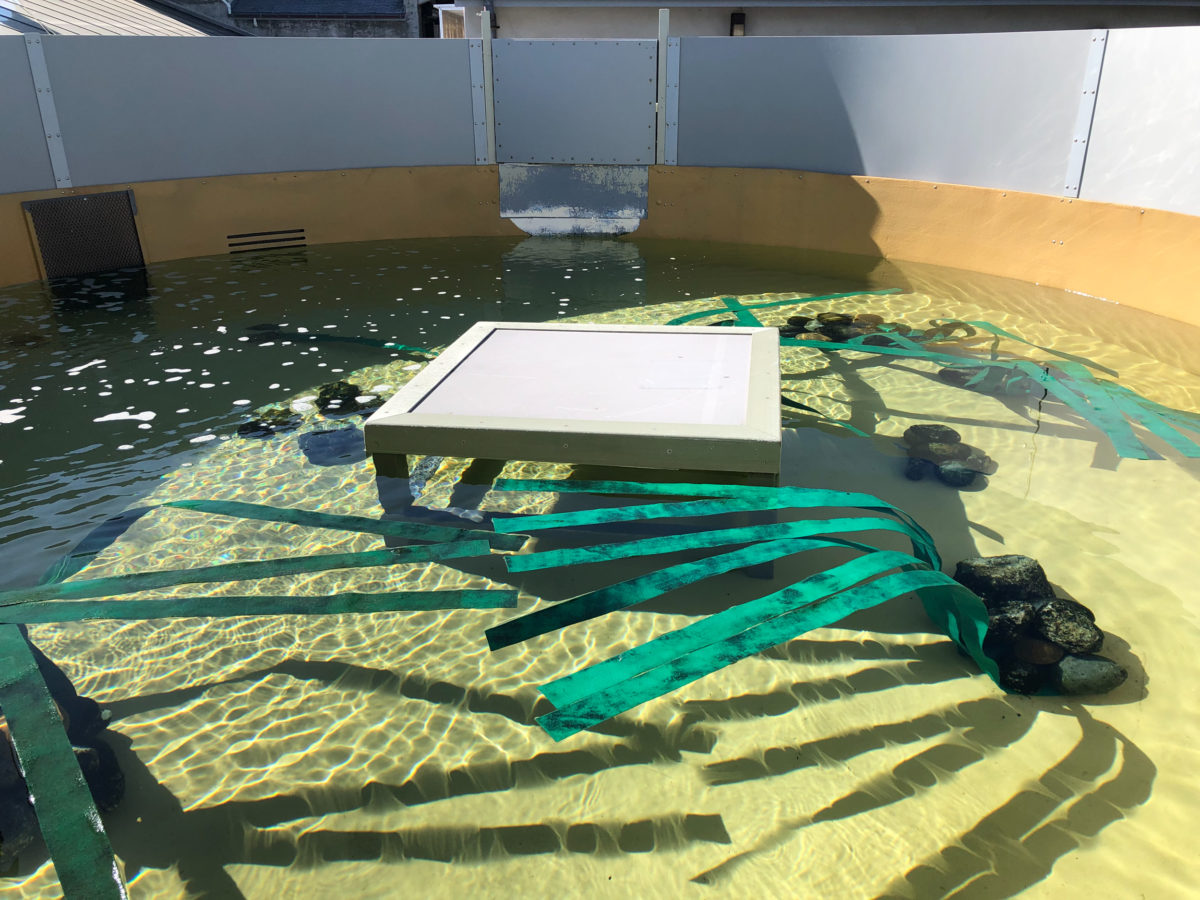

What is so unique about this specific programme, is that even stranded Sea Otter pups, who have been separated from their mother, will later be released back into the wild. This is only possible because the Aquarium pairs the pup up with one of their resident adult female sea otters, who will teach the pup all necessary behaviours for surviving in the wild, such as social behaviours, finding and catching food, or taking care of their coat by grooming and blowing air between the fine hair and the skin (vital for otters, as they are the only marine mammal species which doesn´t have a thick blubber layer for thermal protection).

All Sea Otters with a chance for reintroduction into the wild are also kept in pools equipped with “fake” Giant Kelp, rocks, and other features found in their natural habitat. Additionally, the pool´s walls are non-transparent so that the otters can´t see humans and therefore can´t get used to their presence. For the same reason of not wanting the otters to get habituated to humans, the care-takers would wear wide, black coats and a black helmet covering even their face when feeding the otters. On the other hand, when the otters would have a check-up, an injection or a procedure through the vet, the vet would not cover himself up so as to teach the otters a negative association to humans. As weird as this sounds, this is very important so that the otters as Wildlife animals will keep their respect and distance to the human species after their release.

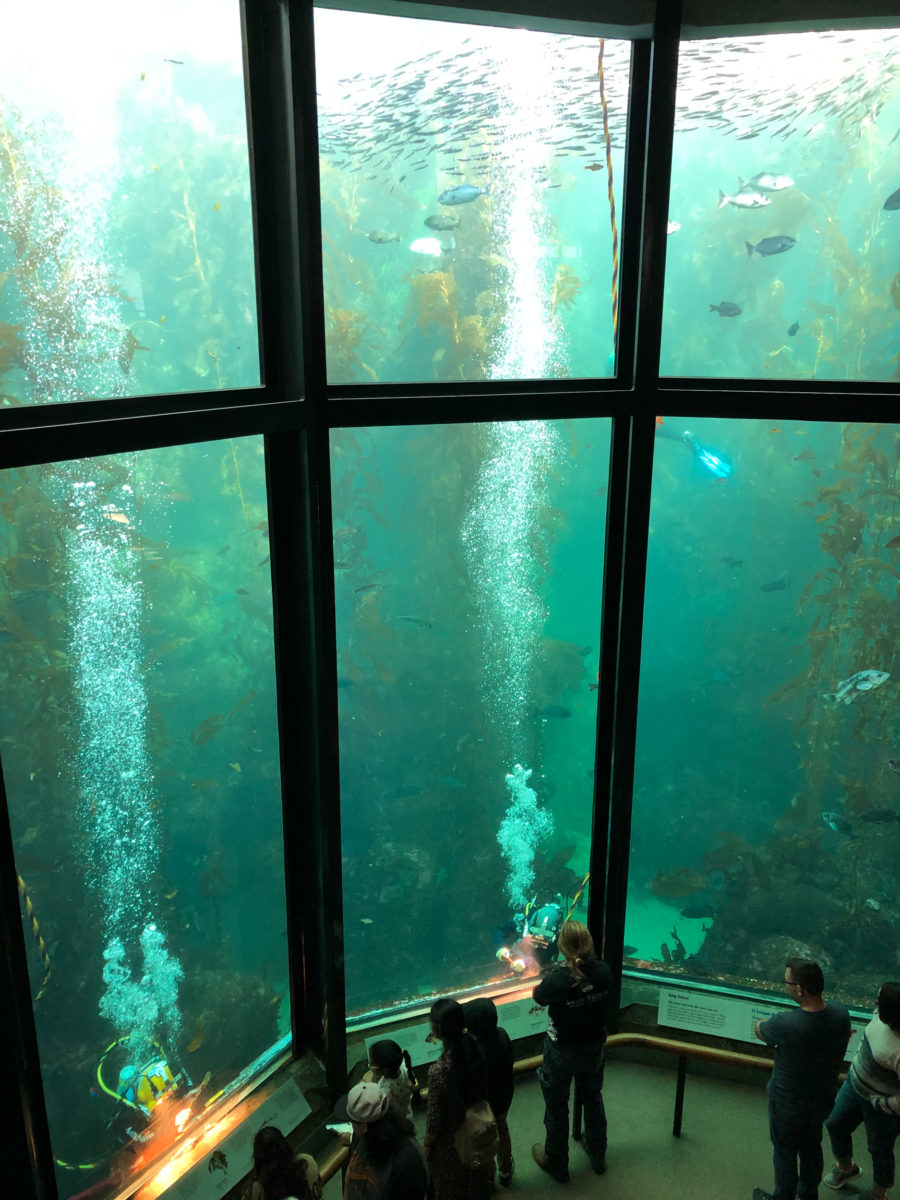

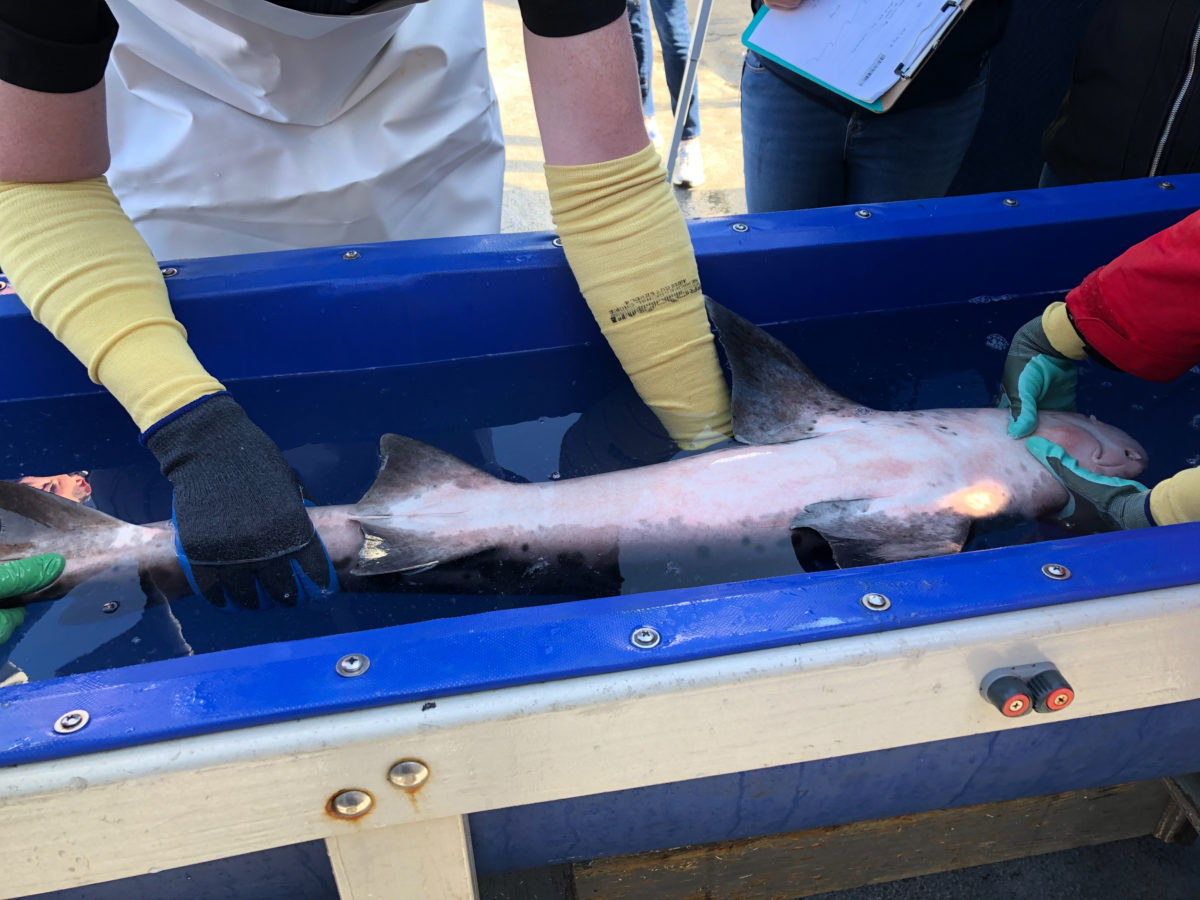

On the day I visited the Monterey Bay Aquarium, there was also quite a big “operation” scheduled: A full veterinary medical check-up of the Leopard Sharks from the big Kelp Forest Exhibition. This required many people to work together: First, the divers from the Dive Department had to catch the sharks with a transparent device, without chasing the sharks so as to minimize stress, which might have negative effects on the sharks´ Anaesthesia which would follow.

As soon as a shark was caught, he was then quickly but calmly put in a bath with diluted Anaesthetic in it. After a few minutes, the shark would have flushed enough Anaesthetic through its gills while breathing, so that it would be calm. Additionally, the shark was put in “Tonic immobility” by turning it with its belly facing upwards, and as a natural response to this position the shark would stay calm and mostly motionless.

Then, Dr. Murray started the check-up with an endoscopy of the shark´s gills, to check for parasites, which like to sit within the gills, and also to check the general perfusion of the gills. Next, Dr. Murray took an Ultrasound image of the thyroid glands, to check for abnormal size, which would indicate a need to alternate the diet of the shark, as a swelling of the thyroid glands indicates a lack of iodine. Lastly, Dr. Murray would take a blood draw and measure different health-related parameters.

After the check-up, the sharks were simply put in tubs with flowing oxygenated water, so that the anaesthetic drug could slowly flush from the shark´s circulatory system, and it could then be released back into the big kelp forest exhibit.

As a little highlight, I was able to join the Dive Team for feeding time in the Kelp Forest exhibit, where Giant Kelp is successfully growing. What is so special about the hand-feed of the exhibits Sharks, Wolffish, and other Fish species, is that one diver is diving with a tethered communication system, which allows this diver to comment on the feed and people watching it from behind the glass front could even ask questions and get immediate answers. A very well-welcomed educational opportunity for all guests!

I learned a tremendous amount about Marine Mammals and the work of a Marine Mammal Researcher, a Conservationist, and a Veterinarian in the field of Aquatic Animal Medicine in California. I was stunned by the programmes I got to learn about and through the insights which I got here, I could very well imagine working in one of these fields in the future! Having accumulated a lot of valuable knowledge and having gained very valuable practical experience, I would like to thank especially Dr. Cara Field from The Marine Mammal Center, Arina Favilla from the Costa Lab of the University of California – Santa Cruz (and Markus Horning for putting us in touch!), and Dr. Michael Murray and DSO Scott Chapman from the Monterey Bay Aquarium, for enabling me to join your institutions and allowing me such deep insights in your fields!