It was 5:45 am. I had just walked up the hill to the restaurant to enjoy the last bits of sunrise and sip on a cup of water before the morning dive. Suddenly, I saw, Sheeka, one of the staff members from the dive shed waving at me from below! “Arzu, come down! Quickly!”, he shouted. For a split second I was worried. What could have happened? I sprinted over to him. “Dolphins in the bay! Look!” I exhaled with relief. With squinted eyes I scanned the surface of the water and then the sight of over 20 dolphin dorsal fins took my breath away. I quickly grabbed my camera and ran to grab a tank and my dive kit. “There’s no time, just grab your snorkel and camera.” Sheeka had done this many times before. Kevin, my dive buddy from the previous days, and I were the only ones still on land. Everybody else was either still sleeping or had already gone diving. With my camera in one hand, fins and snorkel in the other we quickly jumped on one of the zodiacs and then slowly made our way to the entrance of the bay where Sheeka and the dive shed staff had sighted the dolphins. We wanted to approach without scaring them. Just when we thought we had lost them, two dolphins surfaced next to us. Upon establishing a safe area to do so, with ample distance from the dolphins Kevin and I gently slid of the side of our zodiac, only to enter what felt like a different planet.

A few meters away from us the entire pod was playfully gliding through the water, making rapid turns, bolting to the surface, then swimming back down. I couldn’t believe my eyes. It was my first time in the water with dolphins. Previously I had only ever seen them from the deck of sailboats. I didn’t know where to point the camera, nor did I have time to adjust the settings. I saw Kevin’s eyes widen with amazement and was certain my face must have looked the same. Trying to swim after the dolphins was entirely futile as they sprinted through the water so I decided to simply hold my breath, dive down and then hover for as long as I could to watch them. Somehow my attempts caught the attention of a young mother who carefully started circling around me. I felt both humbled and a little bit nervous as mother’s tend to be very protective of their calves. Her eyes fixed on me but with a soft gentle gaze as she and her little one gently approached me while still keeping a safe distance. At one point they were so close that even the dome lens on my camera didn’t manage to fully capture them in the frame. Their grace and speed was a sheer joy to observe. I suddenly felt a bubble hit me from below and chuckled as I watched a group of divers realise there was a pod of dolphins above them. For a brief moment the bubbles stopped as they all looked around in sheer disbelief and one by one they started pointing at the beautiful creatures we shared our time in the water with. One of the dolphins was playing with a black plastic bag. A perfect metaphor for the state of our world’s oceans.

I managed to take a brief video and snap one photo before my camera screen started blinking to notify me that the SD card was full. I hadn’t emptied the card in the morning. I stayed at the surface for a few minutes longer enjoying the magnificence of life around me, until the pod started making its way back to the entrance of the bay and disappeared into the blue. It was an unforgettable morning, both from a personal point of view and in regards to underwater photography. And the latter was why I came to Red Sea Diving Safari in the first place. Usually, the EU scholars spent a few weeks in Egypt at the start of the scholarship year to participate in a series of photography workshops. As a result of the pandemic, Egypt was listed on the UK’s Red List and hence most of this year’s workshops got cancelled. Consequently my photographer mentor Saeed Rasheed and I decided to take an adaptive and blended approach. He introduced me to the absolutely wonderful Sarah O’Gorman, also an underwater photographer who invited me to stay with Red Sea Diving Safari at their main dive village: Marsa Shagra. With a beautiful house reef full of vibrant marine life – from megafauna to tiny critters – and a location that allows for access to some of the most beautiful dive sites around Marsa Alam, it was the perfect base for photography training.

Aerial photo of Red Sea Diving Safari’s Marsha Shagra village capturing the sheer extent of the house reef. Photo by George Nady.

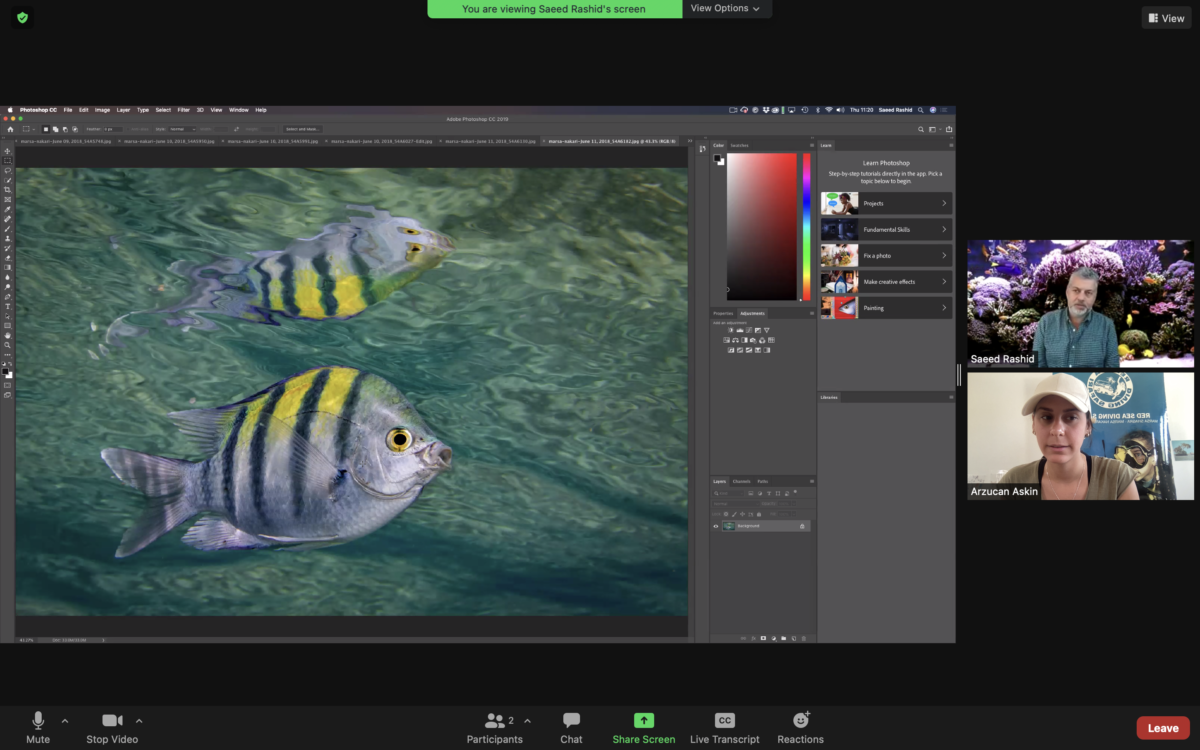

In true pandemic fashion – having first met for a day of a land-based photography seminar in the UK – Saeed and I carried out our training online via Zoom. Equipped with an amazing camera set kindly sponsored by Reef Photo and Video and Nauticam, I spent my days dipping in and out of Marsa Shagra’s House reef, taking photos and sending them back to Saeed for his critical evaluation. With the added challenges of not having a group of photo-buddies who are patient enough to spend an entire dive on one coral or one group of fish, as well as Saeed’s work commitments, we decided to focus on really fine-tuning the basics of photography underwater and on getting me comfortable with my camera. We set a target goal for each week and decided on little challenges I had to complete.

From discussing photography in Bournemouth…

… to hosting Zoom sessions online from Egypt…

… to completing my photography missions underwater, behind every photo was a long process of preparation! Photos by Lou Rasheed and Sarah O’Gorman.

My first challenge was to take split photos without my strobes – easier said than done underwater where most colours disappear after several meters. This was however a very important lesson in assessing the direction, strength and effect of light on my subject.

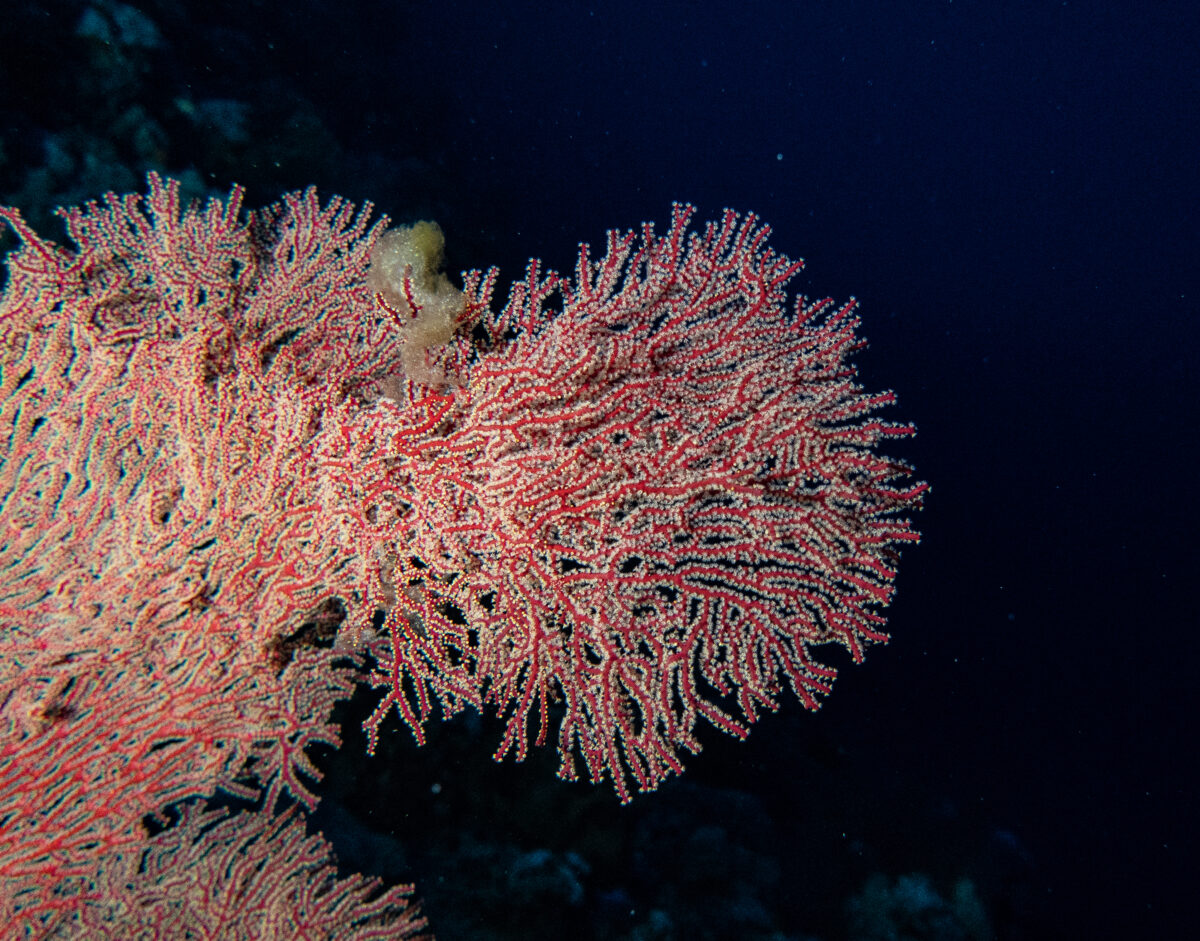

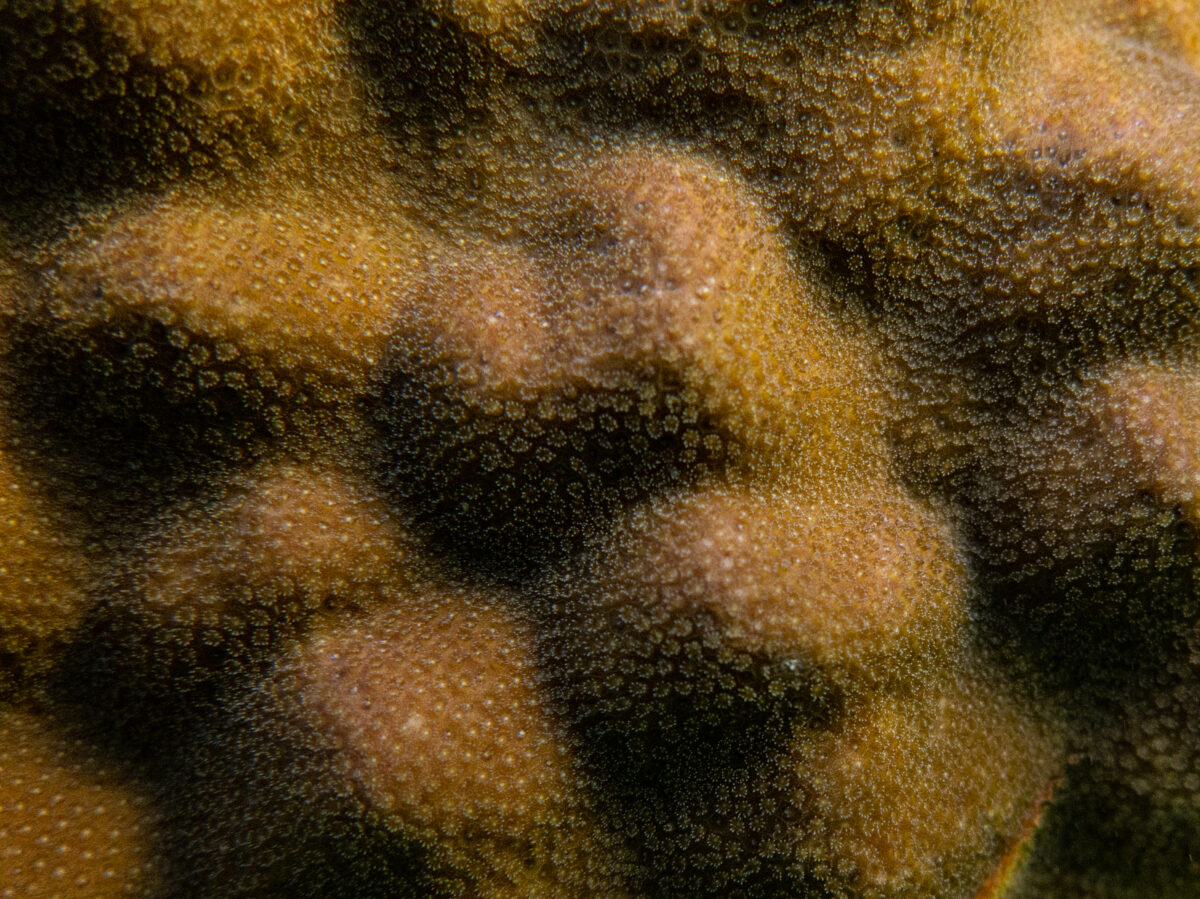

My second challenge was to highlight patterns and textures. I discovered very quickly that I was absolutely in love with macro photography, not only because of the challenge it represented, but also because it forced me to slow down and really focus on the beauty of all the small things the naked eye didn’t seem to notice at first. A reason to slow down (metaphorically and literally), ensure buoyancy is perfect and a perfect reason to practice stillness and patience.

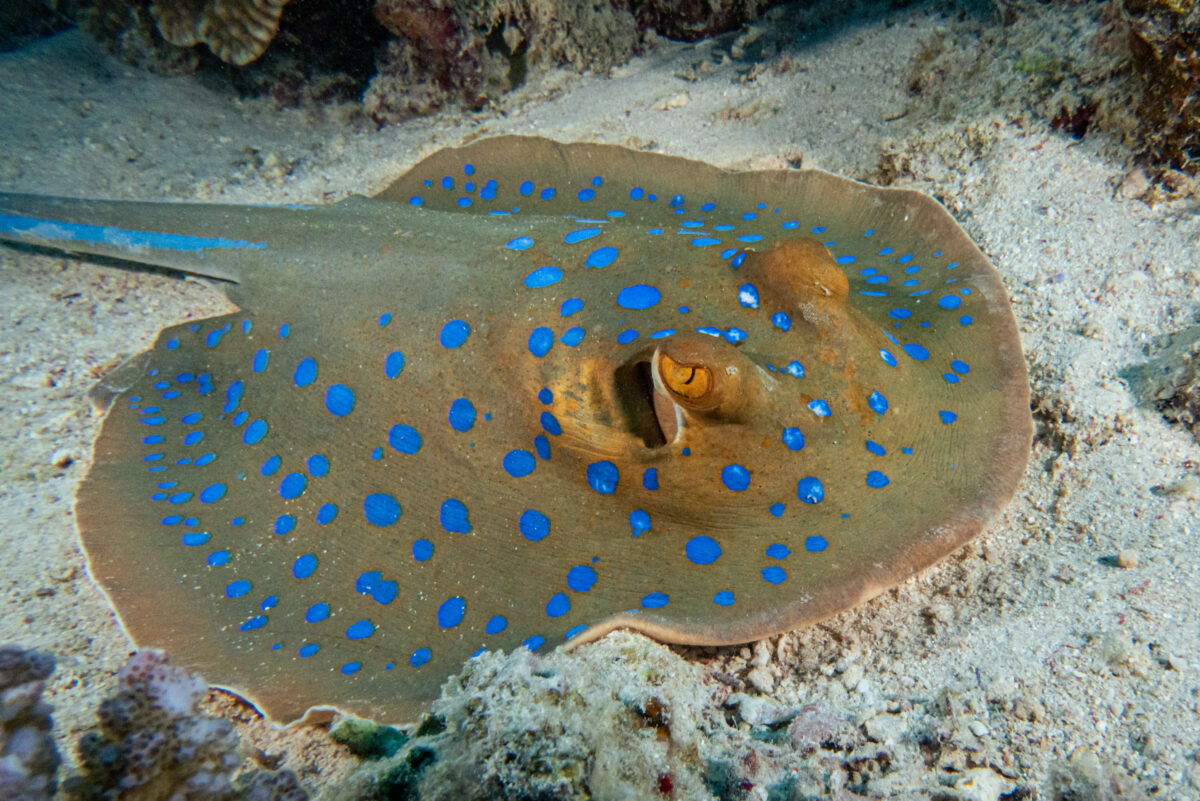

My third challenge was to capture the character of different reef dwellers. Having dedicated a part of my MSc research to “charisma” in animals – defined as their “possession of one or more traits that appeal to us humans – and how subsequently charismatic species become commodified as ambassadors for a defined issue, campaign or environmental cause in marketing and advocacy materials, this was a challenge I deeply enjoyed. For the sake of the taks, I found myself anthropomorphising fish by attributing human qualities to them on a sliding scale of intensity. Saeed and I jokingly referred to a few of them as “Mr Grumpy”.

During my time with Red Sea Diving Safari, we also set a few days aside to cover essential skills and certifications that would allow me to progress further in my scholarship year and serve as first little steps towards technical diving: a nitrox course and a self-reliant diver course, both of which start out with more decompression theory and require a fundamental understanding of concepts such as oxygen partial pressures, surface air consumption rates and redundancy in equipment configurations. Like everything else in a diver’s kit bag and knowledge base, nitrox is a brilliant tool that can be highly effective when used properly, but equally dangerous if not. Its purpose is to increase a diver’s no stop dive time and reduce the amount of nitrogen that is inhaled, allowing for longer dives. In recreational diving terms, enriched air nitrox (EANx) refers to any nitrogen/oxygen gas mixture with more than the 21 percent oxygen found in normal air. For example, 32 percent and 36 percent oxygen are common; often also referred to asnitrox 32 (or 36) or EAN32 (or 36). To clearly identify them from air cylinders, tanks filled with EAN are marked with a yellow and green tank band at the top of the tank. The oxygen mix percentage is written on a label or tag, which is important because the percentage determines a diver’s depth limits and no stop dive time. However, the benefits of Nitrox also come with added challenges that are different from those encountered when diving on air: primarily these are shallower depth limits and the risk of oxygen toxicity. Oxygen, while being the most essential gas for our survival, can become hazardous in high concentrations at pressure. It can affect the central nervous system causing visual distortions, irritability and dizziness, as well as convulsions seizures – potentially fatal while diving. As such, EANx divers not only learn to manage their oxygen exposure, but also have to plan their maximum dive depths according to the percentage of oxygen contained in their cylinders. An absolutely crucial step in this process is the analysis of the oxygen content in their cylinders before each dive.

The joys of Nitrox diving with instructor Ahmed Hassan.

Photos by Estelle Gay.

Nitrox comes in very handy for photography, as it allows me to spend more time below the surface focusing on a particular subject and really get “that” shot! Photo by Sarah O’Gorman.

After my Nitrox certification with instructor Ahmed Hassan, I moved on to the self reliant diver course with Ondine, consisting of both theoretical preparation and dives. At the core it covers the potential risks of diving alone, the necessary precautions and equipment required to manage these risks. It also offered a great opportunity to develop self-rescue skills and new risk management techniques. What I enjoyed the most was the entire process of meticulously planning my dive from start to finish: calculating my surface air consumption rate and managing my gas accordingly, preparing redundant gas sources, informing the dive shed team about my start and finish time for each solo dive and most importantly, learning to handle all the additional kit at the same time as my camera gear and deploying a surface marker buoy with the extra equipment clipped on to me.

Cylinders filled.

Equipment ready to go!

All smiles after my self reliant dive training. Photos by me and Suzy Florida.

Having gotten comfortable with a cylinder on my back and a cylinder on my front side, Sarah offered to arrange for me to take a Sidemount course and experience what it is like to have manage cylinders on each side of my body. As I was planning to dive deeper into technical Sidemount training with Gary Dallas in the UK, this was a great chance for me to come to join his course with a strong foundation instead of starting from scratch. Equipped with my camera kit, my dive gear and my bags, I transferred to Red Sea Diving Safari’s Marsa Nakari village, where course Director Hossam Abdelaziz was expecting me. However, an unexpected little guest also traveled with me: a stray puppy affectionately dubbed “FelFel” (“little pepper” in Arabic). How did I end up with a puppy? Well.. 05:45 am seems to be the time when beautiful surprises are encountered at Marsa Shagra village. One fateful morning at that time, I woke up to the sound of howls and cries in front of my tent, only to find a puppy laying on the rocks by the water. He was wet, his fur crusty from sea salt and his breathing was but a muffled sound. He was so small, most of his teeth still missing, that I guessed him to be about 5 weeks old. I scooped him up in a towel and immediately messaged Sarah, who runs a dog rescue station when she’s not diving. Long story short, the little man ended up staying with me during my time with RSDS and became my surface interval buddy. He also made equipment preparations and cylinder inspections an absolute joy, and without a doubt all guests and staff members fell in love with him. After spending every free minute between dives with him for over 10 days, I was anxious about leaving him behind, so when Sarah suggested I take him with me to Marsa Nakari village, I was absolutely over the moon! And well… what could possibly be better than having a puppy in one hand and an underwater camera in the other? FelFel was great support during my sidemount theory (particularly when asleep!).

FelFel, also known as “the little peanut” helping …

during editing and sidemount readings. Photos. by me

Simply put, “sidemount” is a scuba diving equipment configuration which has scuba sets mounted – as the name suggests – alongside the diver, below the shoulders and along the hips, instead of on the back of the diver. It originated as a configuration for advanced cave diving, as it facilitates penetration of tight sections of cave, allows easy access to cylinder valves, provides easy and reliable gas redundancy, and tanks can be easily removed when necessary. These benefits for operating in confined spaces were also recognized by divers who conducted technical wreck diving penetrations, allowing the diver to pass through smaller restrictions than would be possible with back-mounted cylinders. A common characteristic of the sidemount configuration is the use of bungee cords to keep all the equipment “tucked in” and streamlined. These bungees are normally routed from behind the diver’s upper back to a chest D-ring. The lower part of the cylinder is then secured to the diver’s harness near the waist or hips by bolt snaps clipped to a butt-plate or waistband D-rings. After covering theory, preparing our equipment and going through a long dive briefing that included practicing some of the required dive skills on land, Hossam and I finally went in the water to practice all the required skills: from removing tanks and pushing them in front of us to rescue drills and shutdown procedures. Without a doubt, I look forward to doing more sidemount diving during my scholarship year!

It’s much easier to maintain buoyancy with two cylinders!

Trying the backward finning technique in trim.

Practicing air-sharing drills in Covid times meant not actually taking the regulator in my mouth!

My time with Red Sea Diving Safari was simply unforgettable and I could not have imagined a better return to diving after months spent behind the desk, finishing up my thesis. I learnt many lessons about underwater photography and the benefits of diving with side mounted cylinders. I cannot wait to take these newly acquired skills into the field and continue building on them! It was not easy to leave Marsa Shagra village – I truly felt very cared for by all the staff members and RSDS team – and I am very certain I will come back to visit all the amazing people (and pups) I have met there. Not to mention the absolutely fantastic wildlife at the beautiful house reef (dare I mention that a whale shark visited the house reef and stayed for a while shortly after I departed?)

Thank you so much to Red Sea Diving Safari for inviting me to Egypt! I want to express my deepest gratitude to Sarah O’Gorman for setting up this unforgettable opportunity, and also thank Ahmet Magdy, Estelle Gay and George Nady for capturing photos of me during my training and during special moments. As always, my biggest “thank you” goes to the Our World Underwater Scholarship Society and Rolex for enabling a year of blue learning in the first place, and of course, Fourth Element, Reel Diving and Halcyon, as well as Suunto, Nauticam and Reef Photo & Video for all of the fantastic equipment that makes my underwater explorations possible!