Did you know that for many island cultures in places with large seasonal aggregations of whale sharks, the unique spot pattern of these animals (resembling a starry night sky) has earned them the role of mystical connectors between the unknown ocean and unexplored space? The cosmological significance attributed to the animal is also reflected in the local names given to them. In Madagascar, for example, whale sharks are referred to as “marokintana” (Malagasy: “many stars”). Likewise, the Javanese name for whale sharks is “hiu geger lintang,” translating to “fish with stars on its back”.

The widespread perception of whale sharks as swimming “undersea constellations” is not only part of long-standing oral traditions in coastal cultures but has also found its way into contemporary science. And here is where the magic happens: The spot patterns on each whale shark are as unique as human fingerprints; and the software applied by researchers to identify individual whale sharks was developed in collaboration with NASA astronomers and adapted from the star-matching algorithm used by the Hubble space telescope.

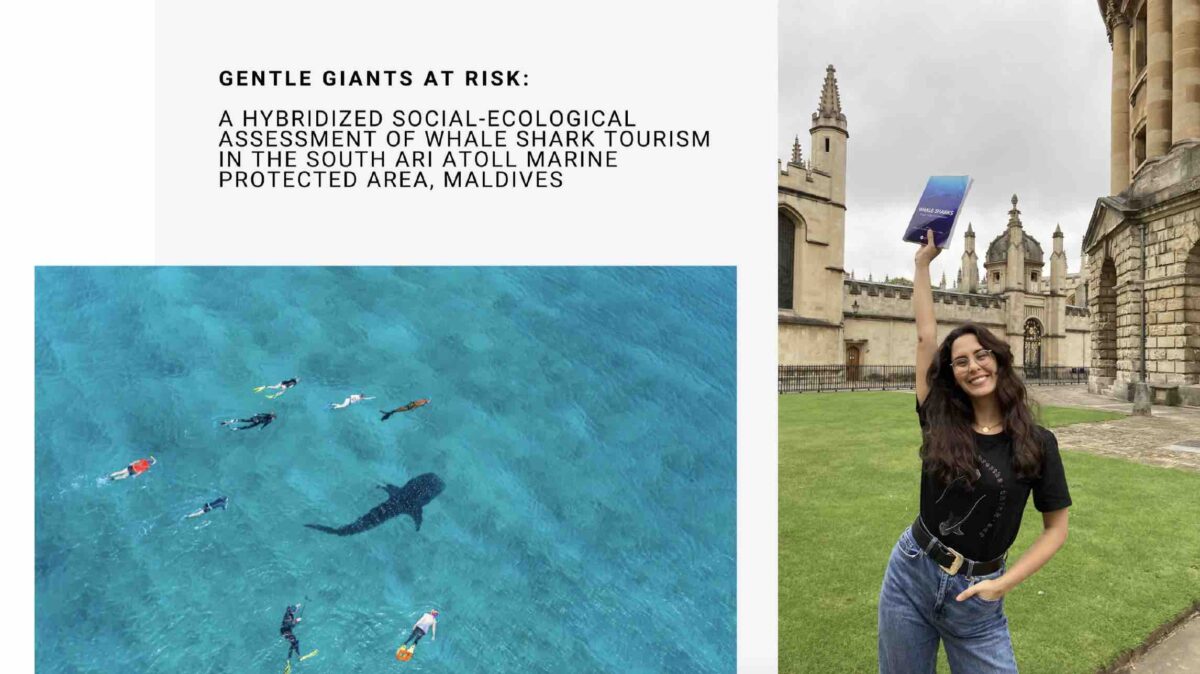

At this point, many of you will already know that my entire MSc degree was dedicated to sharks and that my thesis research focused on the impact of human activities on whale sharks specifically. Before embarking on my scholarship year, I spent my summer months analyzing whale shark injuries from collision with vessels and examining tourist interactions with the gentle giants. Hence, when I found out the Maldives Whale Shark Research Programme (MWSRP) had a spot free onboard its research vessel in the South Ari Atoll Marine Reserve (SAMPA) I knew that my next stop would be the Maldives.

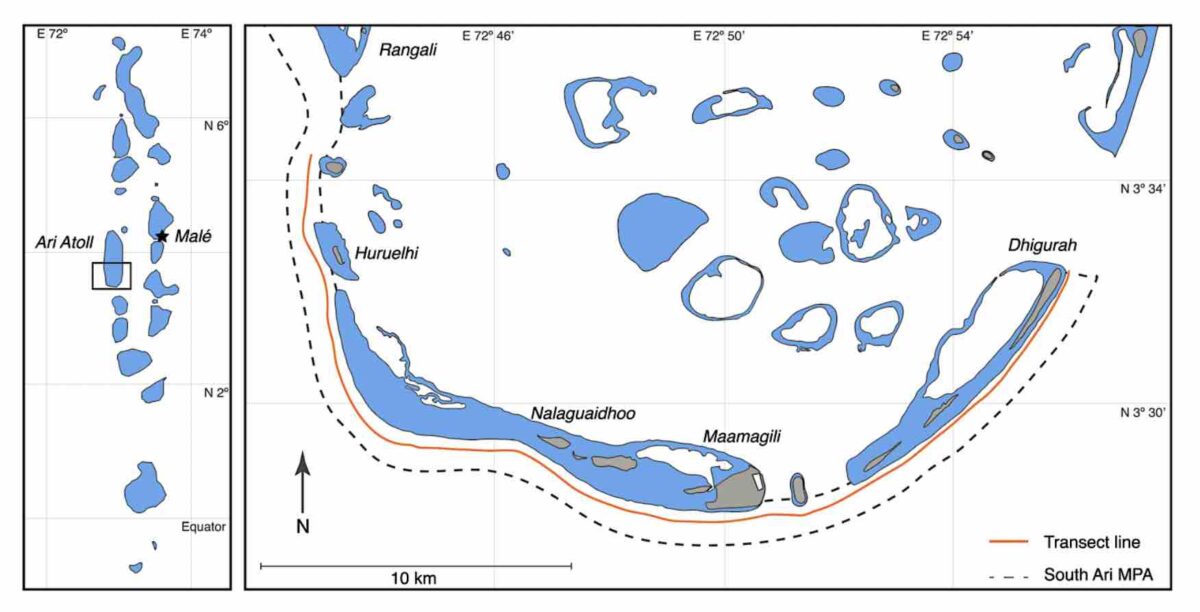

The South Ari Atoll Marine Protected Area (hereafter referred to as SAMPA) in the Maldives is a globally significant aggregation site for whale sharks. Unlike other aggregation hotspots that witness seasonal whale shark movements such as Mexico, SAMPA is globally unique due to its year-long presence of large numbers of whale sharks. Past research by the MWSRP has determined that the sharks exhibit significant levels of residency and a tendency to return to sites on the southern fringes of the atoll. The frequency of and regularity of whale shark sightings has also made SAMPA a popular destination for divers and snorkelers wishing to observe this species. In the Maldives, tourism industries enabled by whale shark encounters have grown rapidly and provide significant economic value, yet remain largely unregulated, with severe impacts on these beautiful creatures.

Wanting to continue studying the consequences of human activities on these endangered animals, I joined the Maldives Whale Shark Research Programme (MWSRP) for two weeks of whale shark monitoring in the MPA. From morning to late afternoon we surveyed the entire MPA along a transect. We collected data on the whale sharks within the MPA, any injuries they have sustained from collision with boats, as well as the number of vessels and tourists present during whale shark encounters.

The extent of human pressure on these sharks became evident on day one already, when we logged more than 10 vessels, each with an average number of 15 tourists onboard, crowding one whale shark. For the next two weeks similar stories unfolded and our concern for the sharks grew steadily when observing vessels speeding through the MPA, injuring sharks in the process.

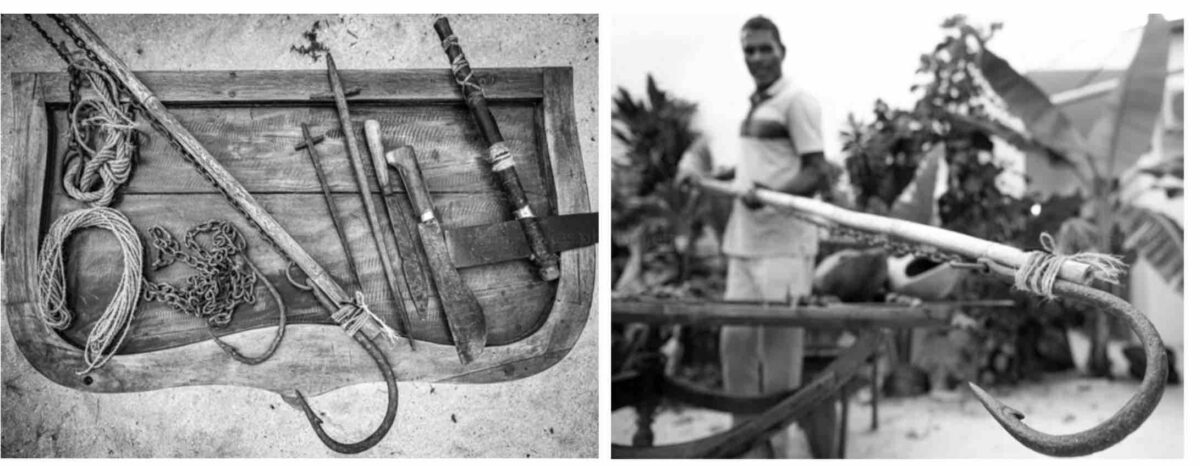

How is this possible in a Marine Protected Area? Well… SAMPA currently exists as a ‘paper park’ with no management plan implemented to date by the island council or Maldivian authorities despite ongoing discussions between stakeholders. I had the opportunity to address this issue during a presentation of my MSc thesis where I shared the insights from my research that examined the complexity of human-whale shark interactions in the Maldives, covering tourism, fisheries and the dive industry, while also taking an anthropological approach that examined the tradition of whale shark hunting in the past.

Wherever possible, we also conducted freediving surveys to collect Photo-IDs and identify the sex of the whale sharks to build on the MWSRPs long-term monitoring database. Every evening, when it was time to enter all of our data from the day into the MWSRP spreadsheets, and then run the ID software to cross-check for potential matches, I could not help but smile and think back to NASA’s role in the development of the technology we now use for conservation. During every encounter we also collected data on environmental variables in situ, including cloud coverage, wind speed and direction, sea surface temperature and visibility. Cyclical and climatic shifts have also been shown to affect occurrence and abundance of whale sharks, and the individuals in South Ari Atoll particularly are now known to show monsoonal movements across the atoll.

My time with the MWSRP has been full of lessons regarding the uncertain future of this endangered species. SAMPA provides critical habitat for whale sharks and if managed well, potential shelter for juveniles. Not only does the current pressure from tourism impede feeding and thermoregulation behavior, but it also jeopardizes the health of the population in the future. What was most tragic to see was that on top of whale shark tourism’s effects on the ecology and behavior of these animals, current practices also reduce the economic sustainability of the industry. A decline in the very species responsible for attracting tourists is bound to impact local development. Successful whale shark tourism in SAMPA needs to protect wildlife and their habitats while balancing the associated social and economic values.

I cannot thank the Maldives Whale Shark Research Programme enough for inviting me to join their fieldwork and supporting me in the collection of more data for the publication of my research thesis. I would like to particularly thank Chloe Darwin who led our scientific efforts and never ceased to inspire during long hours at sea, as well as Clara Canovas Perez who not only provided core contributions to my thesis research, but also coordinated my participation in this research expedition. My gratitude also goes to the Our World Underwater Scholarship Society and Rolex for their support in making opportunities like these happen, and my amazing equipment sponsors Fourth Element, Halcyon, Reel Diving, Reef Photo & Video, Nauticam and Light & Motion for the brilliant kit that I used during the fieldwork.