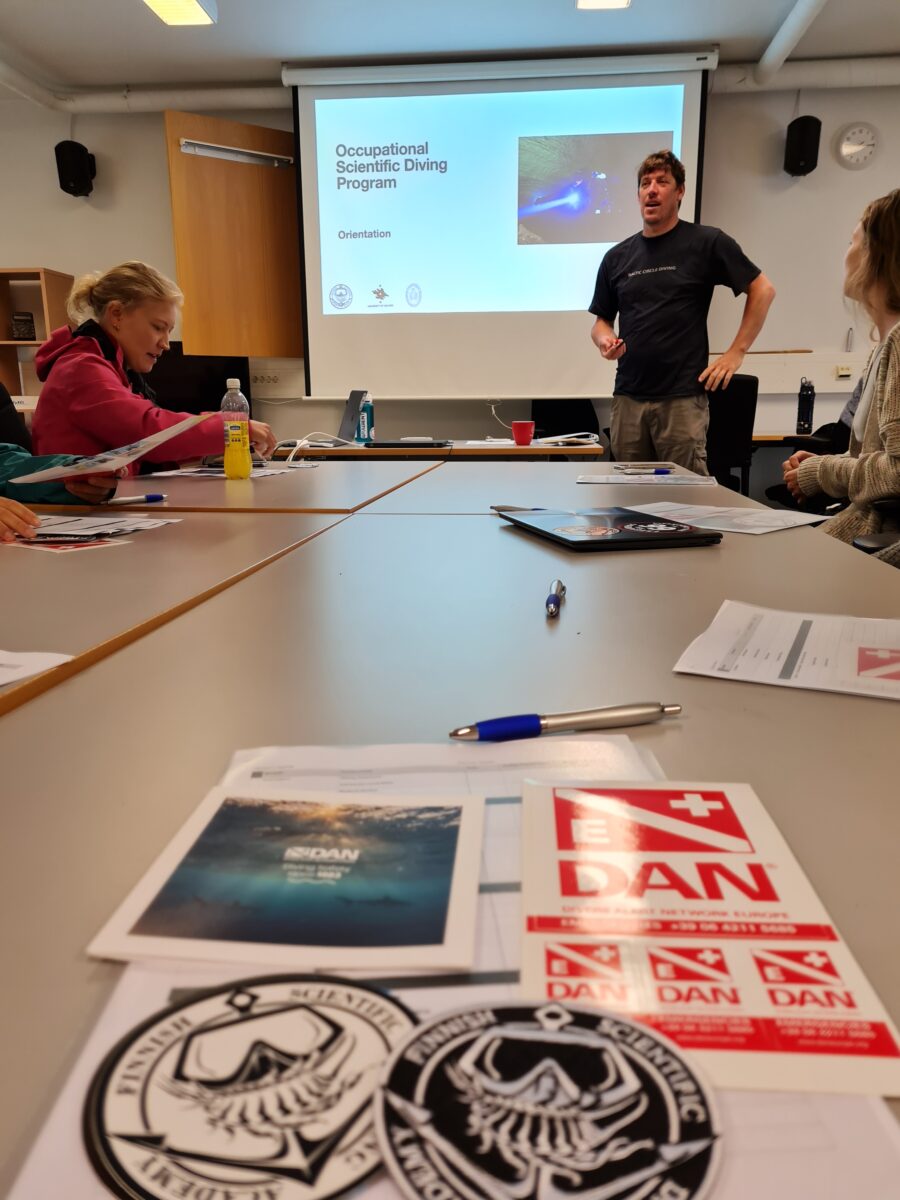

This Summer, I spent the months of August and September in Southern Finland in the Tvarminne Zoological Research Station taking part in Occupational Scientific Diver Training in the Finnish Scientific Diving Academy.

The Tvarminne Zoological Station is at the heart of a long standing nature reserve. Which means that the amount of pristine wildlife we saw during the course was amazing; both above and below water. From the deer which came in the evenings to munch on the apples hanging low in the station’s trees, eagles wheeling high above to pipefish, nudibranch and the fascinating saduria, a native crustacean that appears as a leftover from the prehistoric era.

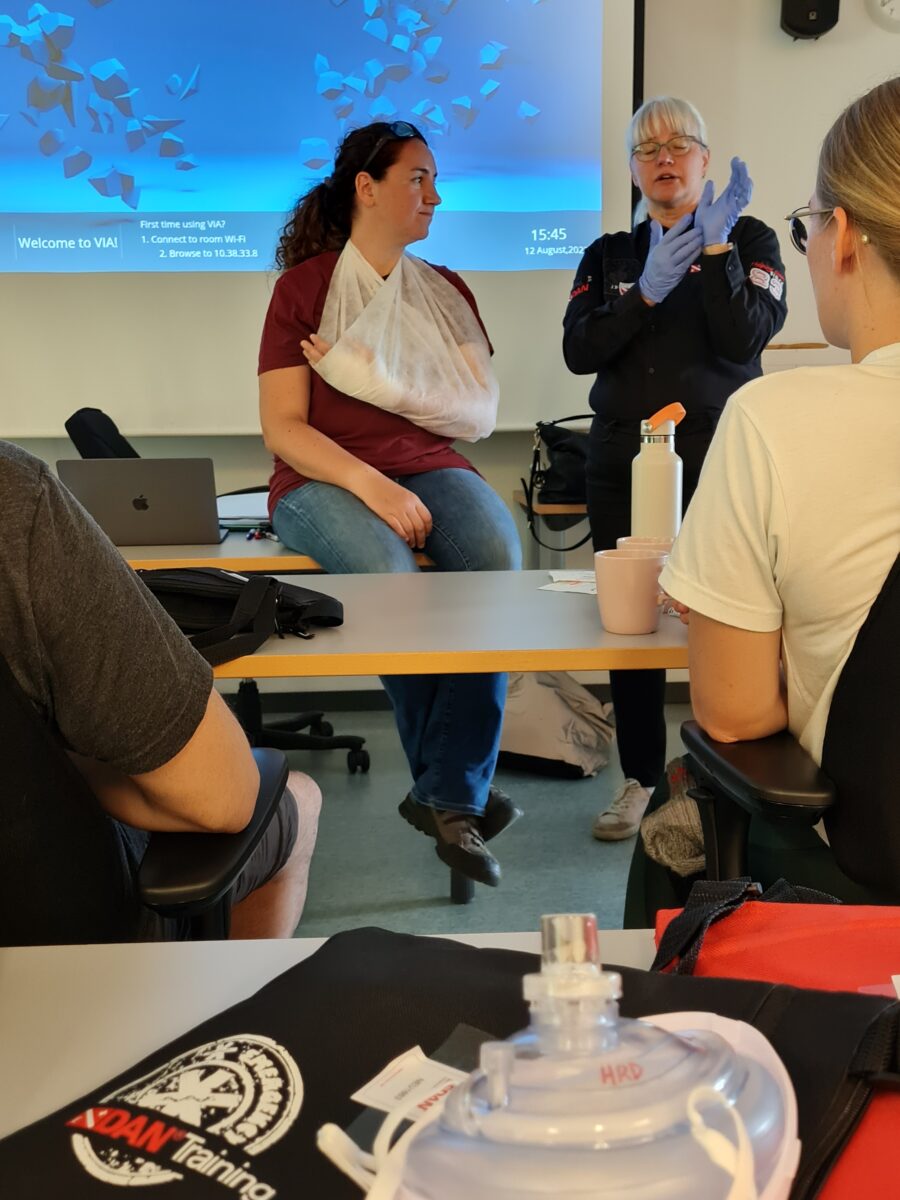

The course is a combination of classroom lectures, practical diving and report writing. We began in August with general diving skills, working out kinks with buoyancy control, back finning and learning new equipment setups like diving with full face masks and surface tether lines. We also had training sessions on equipment servicing, like how to find the leaks and patch a drysuit or how to know which o-ring needs changing in a first stage. Specialists came to the station to cover several topics, we were lucky to have training from Anne Räisänen-Sokolowski, a leading hyperbaric doctor on basic life support and first aid, oxygen and advanced oxygen administration and how to conduct on-site neurological exams for divers with suspected Decompression sickness (DCS).

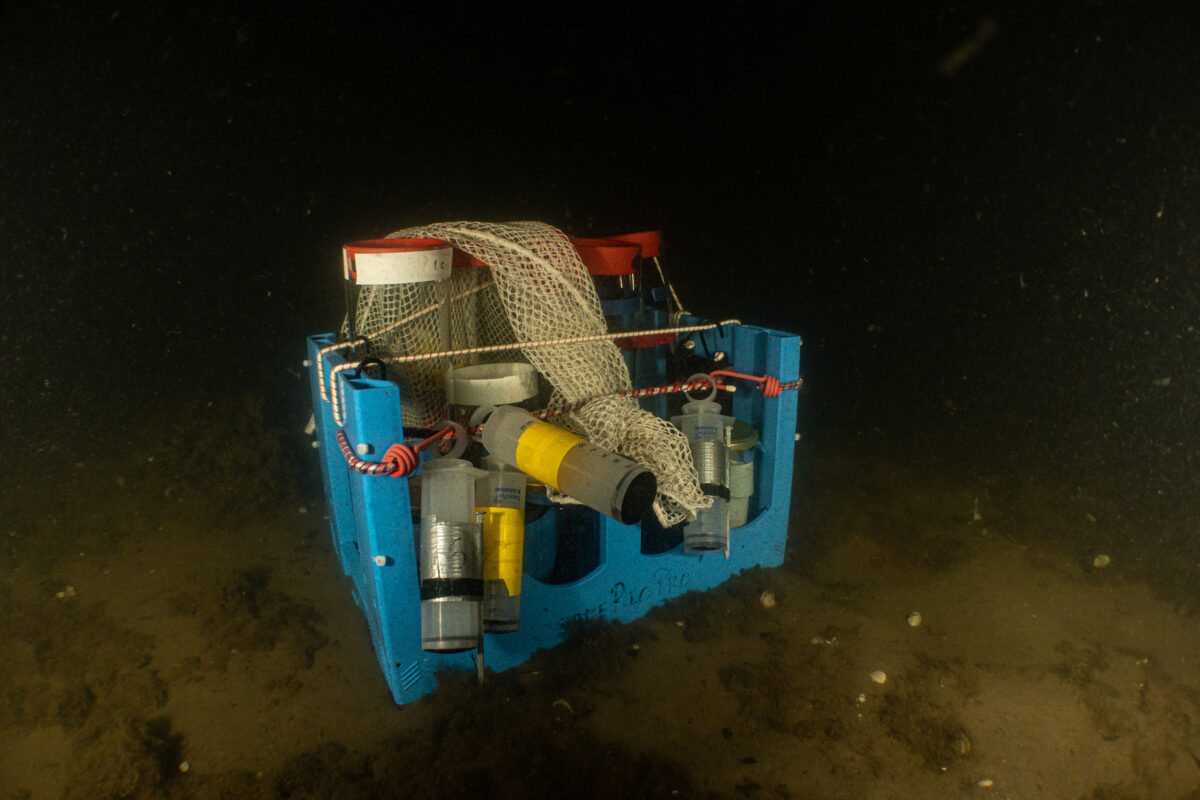

Soon we moved onto scientific diving techniques; transects, quadrats, video and photo data collection, photogrammetry, sediment coring of various types, lift bags, air lifts, kautsky quadrats and more. Each day we were covering a new data collection technique, theory and implementation.

In addition to new scientific techniques we also covered new diving techniques and equipment set ups, like diving with a tether line to the surface for communication via line pulls. We also had the opportunity to learn how to dive using full face masks with through-water communications. Being able to communicate detailed information underwater both between divers and between the divers and the surface opened up a whole new range of possibilities. It was brilliant to be able to continue diving with the full face masks and build up our comfort and skill at using them.

While soaking up science diving knowledge, it was lovely to experience the culture of the Finnish people during the course. Each Wednesday and Sunday we had sauna nights where we would run from the heat of the sauna to the jetty and jump into the Baltic sea, then hop back into the sauna again, repeating the process a few times, at the end of which everyone felt like a new person, refreshed and ready for the next day. In mid-August we also went blueberry picking in the forests around the research station and I had the joy of experiencing pea soup and pancake Thursdays which is a staple and weekly tradition.

Even though we were in a very southern part of Finland, I was lucky enough to one night be awoken by a hushed voice, alerting me to a magical show occurring overhead. The aurora borealis, in a white, shifting pattern out in the distance on a perfectly clear night.

We spent time learning boat handling and built up our independence during the course until we could each navigate the intricacies of the Hanko archipelago. This is a challenging stretch of Baltic, Archipelago Sea due to the numerous small islands and underwater rock formations. In fact this area is well known for its huge number of historical wrecks, and due to the low salinity of the area many of these wrecks are incredibly well preserved, dating back to the 17th century.

In addition to the practical diving, we had plenty of writing to do. Each evening in groups we developed our own diving policy and procedures, we wrote risk assessments for scientific diving and emergency action plans. In this way we experienced every aspect of planning, developing and implementing our own scientific diving operation.

Towards the end of the course, we were given various assignments, like research questions for which we then had to develop a hypothesis, data collection and diving plan and then write up a short thesis style report.

During this period of group work, I was involved in a habitat mapping project, where we surveyed a seagrass (Zostera marina) habitat using a new underwater GPS technology called a UWIS. This technique involves deploying three buoys which take GPS information and employs a process called triangulation to locate the diver unit. This is achieved via ultrasound underwater. After deploying the buoys, we brought an underwater modified tablet and UWIS tracker and were able to use the tablet while on the dive to record GPS data for edges and patches of seagrass.

We were hoping to locate an area within the seagrass meadow for the deployment of a new permanent data recorder buoy. MONICoast is a coastal monitoring system of buoys around the Hanko Peninsula which record temperature, salinity, oxygen, pH and turbidity. Based on the data we collected and our GPS location proposal report, a new MONICoast sensor buoy is set to be installed at the proposed site in the seagrass meadow.

In our final weeks on the course we carried out two other independent research projects. One assessed the diversity of epifaunal growth on various marine substrates, shipwrecks and submarine cables as compared to natural rock formations. The other focused on a sessile (unmoving) benthic (seafloor) species, blue mussels (Mytilus edulis). We collected mussels from a variety of depths and compared their abundance and size distribution.

Each of these projects had their own challenges, but each time we overcame these there was a huge sense of achievement. Without a doubt, learning in this hands-on way will be invaluable when it comes to setting up my own independent research projects.

My time in Finland was filled with growth and learning both due to the well structured course with lots of practical hands-on learning opportunities and expert instructors, but also simply because of the magic of the location. I am excited to have found such a beautiful corner of the world, I hope to someday return and continue conducting underwater science there.

Thank you so much to everyone at Tvärminne Zoological Station and the Finnish Science Diving Academy for making me feel so at home during my time there and for helping me to learn so much. Also thank you to my awesome course mates, we did it and I will miss you all dearly!

Thank you to Rolex and OWUSS for making dreams come true. Also thank you to my incredible equipment sponsors Fourth Element, Suunto, Halcyon Divesystems, Reef Photo and Video, Nauticam and Reel Diving.